(David Cameron / Photo: Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street)

By Andrés Ortega

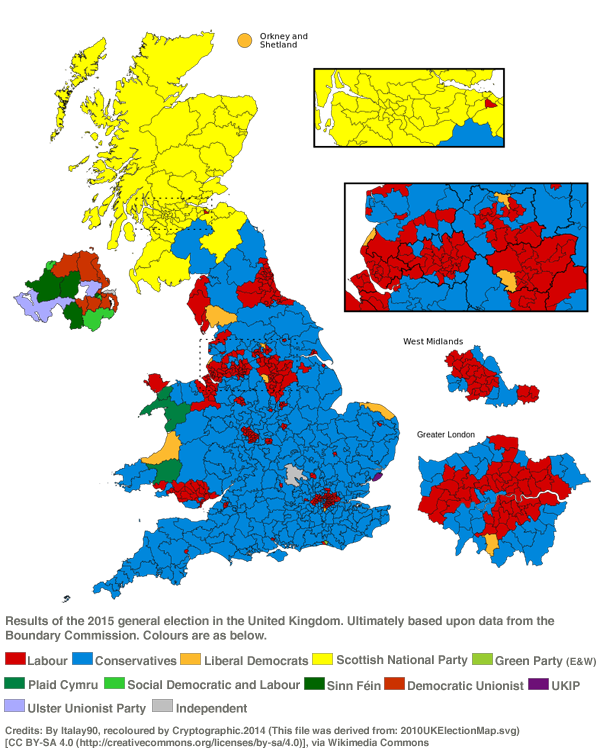

Despite the official congratulations, Europe’s conservative-dominated collective leadership would have rather seen Labour’s Ed Miliband entering 10 Downing Street. This might seem a paradox, but it is not. There is little confidence in David Cameron. First he got Scotland into an independence referendum that made much of Europe very jittery. Europe’s leaders will again feel a shudder down their spines once the British referendum (Brexit) on leaving the EU comes up. Although Scottish nationalists only just lost their referendum, thanks to devolution promises Cameron now has to honour, the effect has been a totally SNP-dominated political landscape in Scotland. In last Thursday’s general election the party swept the board, taking 56 of a total of 59 seats, compared with only six in 2010.

Following the uprooting of the Conservative presence in Scotland since the Thatcher era (limited to just one seat, like the Lib-Dems), the turn has now come for Labour, which has also retained a single constituency in what has been one of its strongholds for the past 20 years, having won 41 seats in 2010. Thus, there is again the prospect of a break-up, or at least a wider split, in the UK, particularly given the Tories’ determination to not allow Scottish MPs in Westminster to vote on exclusively English matters.

The Scottish question will continue to be important over the next few years and it will be further aggravated by the issue over which Cameron generates mistrust in Europe: the promise of an EU in/out referendum by 2017 (although it may be delayed). The Scots are more pro-EU than the English, and this will favour a break-up if there are prospects for a Brexit, as they will want to remain in Europe. Brexit and break-up will be very much at centre-stage in the UK over the next legislature. Furthermore, although the UK is not in the Eurozone, the issue will be at the heart of European politics also, despite the many other problems the EU must confront.

The country has emerged more anti-European from these elections (although Europe was not the issue). The UK Independence Party (UKIP) may have only gained one seat due to a cruel but effective electoral system. But it has come second in many constituencies and managed to attract 12.6% of the total vote, a nearly 10-point swing. Beyond this, Farage has contaminated British politics with his anti-European and anti-immigration discourse. Although Cameron has won, he now has a very Eurosceptic parliamentary group, which has already forced him to commit to a referendum that could lead to Britain’s exit from the EU. And he will no longer count on the moderating pro-European influence of his former partner in government, the seriously-damaged Lib-Dems.

Aside from the migration issue, anti-Europeanism is more of a problem within the Conservative Party itself than is society at large. The latest polls show a majority of Britons in favour of remaining in the EU, though perhaps in a watered-down version that repatriates powers from Brussels to London. The gap between pro- and anti-EU is not, however, all that great and it would be well to remember how things developed in the run-up to the Scottish referendum. Support for a referendum on the EU has declined but there is sure to be one. Cameron has pledged to campaign in favour of remaining, but also to trimming down the EU, at least in the UK, and this is something that today the rest of the Member States and European institutions will not concede. Nobody wants to reform the treaties –as it would involve national referendums– before, at the earliest, 2019. Nor is the EU (the Eurozone is a different matter) willing to go much further as regards integration.

It remains to be seen what the rest of the EU will do when the moment of truth approaches. It is aware that without the UK the EU loses lose international, military and even economic and financial weight. Despite being outside the monetary union, the City of London is still the euro’s financial centre.

A more fragile UK in a weaker Europe suggest a worrying prospect for Europe in political terms now that the economy is finally on the mend. It is not just that Cameron’s electoral triumph compromises the UK’s future in the EU but it also jeopardises the future of the EU itself. But in Europe, once the economic pressure is down, political risk goes on the upswing.

Andrés Ortega is Senior Research Fellow at the Elcano Royal Institute. He is also an independent consultant and director of the Observatorio de las Ideas. @andresortegak

Note: This article was published on Andrés Ortega´s blog “Global Spectator” in Elcano Royal Institute.