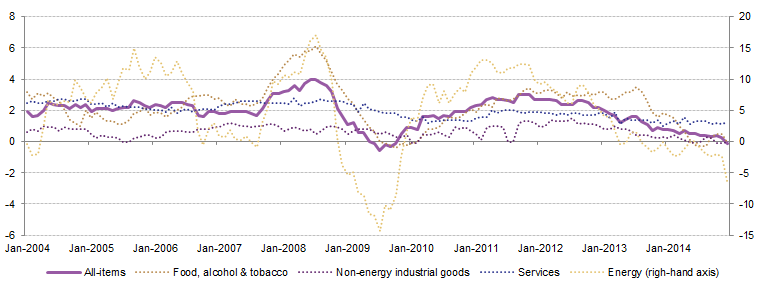

In the past inflation was the number one enemy of economists. Nowadays, you might find that the exact opposite is true, and that a fall in prices is now in the spotlight. Deflation has arisen as the main threat to the economy, and the European Central Bank (ECB) is under pressure to take decisive measures against it. Prices in the Eurozone have seen the first year-on-year decline in five years, according to Eurostat.

The Harmonised Consumer Price Index ended 2014 on a negative 0.2%, driven by a sharp fall in oil prices. Moreover, more than a third of the products in the ‘shopping basket’ – which is composed of the most popular products purchased by Europeans – are depreciating.

During the first ECB meeting on monetary policy of 2015 its President Mario Draghi will be confronted with this figure, and will feel pushed to start an unprecedented purchase of sovereign bonds – known as Quantitative Easing (QE) – aimed at boosting growth and inflation.

After several months, Draghi has finally acknowledged that deflation is a real threat that cannot be “ruled out completely”.

In a recent interview with the German newspaper, Handelsblatt, the Euro’s guardian has said that “the risks of not fulfilling our mandate of price stability are in any case higher than they were six months ago”. He has also admitted that the ECB Governing Council unanimously agrees on taking additional measures to tackle the persistently low inflation, and that the target for the inflation rate is now set at nearly 2%.

Experts agree that even if the ECB takes action at its next meeting on 22 January, the effects of QE would come too late and would not suffice anyway. Nobel Prize winning and Princeton University professor, Paul Krugman, thinks that “the Euro area has entered a Japan-style deflationary trap”. After more than a decade of deflation and stagnant growth the Japanese economy re-entered into recession in 2014.

Downward spiral of falling prices

Deflation may seem a positive phenomenon for consumption. Why should we be afraid if the Euros we have in our pockets provide increased purchasing power? Simply because when deflation settles in future price falls are foreseeable, and therefore purchasing decisions are postponed. In the meantime, businesses postpone investments and stop hiring, driven by low consumption levels. The decline in sales also affects tax revenues, restrains wage increases, and reduces profit margins. Deflation strangles borrowers because they find their debts increasingly hard to pay back, and this affects the most indebted countries in the region as well.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has warned about economies particularly vulnerable to deflation, including the Eurozone, and has heightened fears about the negative effects of a period of ‘stagflation’.

“If inflation is the genie, then deflation is the ogre that must be fought decisively,” IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde said in January 2014.

In fact, it’s easier for the ECB to fight inflation than to fight deflation. When prices soar the only thing the central bank has to do is raise interest rates, and then lower them back once the economy has cooled down. However, it is difficult to find a magic bullet when trying to avoid deflation, even more when there is so little room for maneuver with close-to-zero interest rates in the Euro area hitting an all-time low.

Sovereign bonds purchase programs, such as the ones that have been a stimulus for the economies of the United States and Japan, have had some unwanted side effects too. The money coming from these liquidity-providing operations has been channeled to the capital and real estate markets, increasing the prices of those assets more than the prices of consumer products, and raising concerns over the risk of new speculative bubbles.

Despite everything, the ECB has implemented non-standard measures such as the purchase of private debt in order to boost prices. But markets now demand Draghi to bring in the big guns at the 22 January meeting, just three days before a possible electoral victory of Syriza in Greece, which would pose a threat to the future of the monetary union.