Especially in times of populism and growing right-wing movements, artists hold a mirror up to societies and sense tendencies long before these become conscious.

Stine Marie Jacobsen is an artist and also a human dynamo. She pours her immense resources of energy and imagination into a staggering range of projects, from best-selling German phrasebooks for expat artists and other newcomers to collaborative workshops exploring the relationship between violence in movies and in our lives. In the work Direct Approach she asks people to describe the most violent scenes they have seen in films and then to re-enact them, playing either protagonist or victim.

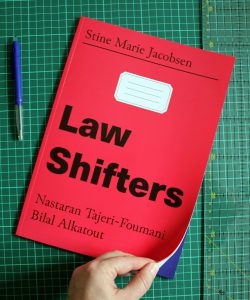

More recently she has developed a project which addresses the law, allowing school students, immigrants, refugees and ordinary citizens to rewrite verdicts and decide sentences in past cases and also (with the help of lawyers) to draft their own laws for public display and debate. The project is called ‘Law Shifters‘ and she spared some time from her bewilderingly busy schedule to tell Katoikos about it.

Richard Willmsen: What inspired Law Shifters?

Stine Marie Jacobsen: In 2013 I was invited by Air Antwerpen to come to Belgium as part of an artist residency and work on the growing right-wing tendency in politics. I started having conversations about this with a broad range of citizens and would during the interview ask them to compare their observations to a film they had seen. My trade mark!

The citizens spoke to me about a sanction law that enables municipalities to hire citizens to subjectively give other citizens fines, the so-called GAS (Dutch: ‘gemeentelijke administratieve sanctie’), for whatever they deem as a “public nuisance”. GAS was supposed to unburden the police from “petty crime”, so they could focus on tougher cases. GAS was written in 1999 by a lawyer called Luc Van den Bossche, who was inspired by the British ASBO (Anti-Social Behavorial Order). The citizens are only trained 8-15 hours, and the result was abuse and overuse.

Municipalities as well as police stations started getting back reports saying “frozen ice”, “man honking too loud at his wife”, “boy mimics siren” (no kidding, I tried to interview him but he wanted to be anonymous), “teenager eats sandwich and crumbs on church steps”, etc. GAS had been also used to target especially protestors and immigrants, Peace Judge Jan Nolf told me in an interview.

It literally sounded to me like the surrealists had come back to Belgium, but alas it was the cruel reality of laws going too far. This made me interested in the “condition of law” and from here Law Shifters started.

How does this project work?

The Law Shifters sessions depend on “stakeholders”. If they are students, I and a lawyer “warm them up” by inviting them to re-judge a real court case and to discuss their verdict with the original verdict. We use court cases as historical or current documents as a way of looking into how we behave towards each other and how that might have been changing.

For example, what was considered an unacceptable racist remark in 1980s might no longer seem too bad to a young person now, among others because they can read adult citizens writing “let them drown” about refugees.

If the participants already are “carriers of need or knowledge”, we go straight to discussion and law writing. The second part is that a lawyer translates these laws into official law language. These laws are then either carved into walls, floors or displayed on street posters.

Which responses to the project have been most surprising and rewarding?

One Syrian teenager surprised me when he asked: “But is it okay to write one’s own law?! It will not hurt my asylum application, will it?”

As for rewarding (not that I suffer from a saviour complex…), it was when a refugee in France said: “Thank you for listening to my needs and for treating me like a human”, or when a street worker from my collaborator Gangway heard a German pedestrian react to one of our street posters as follows: “Wait, is this a real law? Since when does the German Government display its laws in public?”

Are you aware of the work of Augusto Boal, specifically his Forum Theatre and the Theatre of the Oppressed?

Of course, I know both Boal’s work and the writings of his “forefather”, Paulo Freire. Law Shifters does empower participants in a similar fashion.

However, it seems to me that I can detect in Augusto Boal’s texts and methods a tendency to search for and use the idea of ‘absolute evil’. In Direct Approach, on the contrary, I do utilise the terms ‘victim’, ‘perpetrator’ and ‘bystander’ to trigger chaos, but in general I try to use such morally charged terms very sparingly.

I don’t think we can ever offer answers as if we had a standard morality. So we need designs that are more correlative, associative and organic. But maybe I misunderstand Boal and Freire and need to read more of their work.

To what extent is your artistic model transferable; could it, for example, be turned into a school textbook? Would it work as well in such a framework?

Yes, it could work well as a textbook. As a matter of fact, we made one in 2016 in German about Immigration Laws. You can access it here, and please feel free to share it! I also plan to make a publication with Flat Time House in London during our Law Shifters collaboration in April–May 2018, so if you know of any funds we can apply for, let me know!

If in the meantime there are educators or indeed anyone who wants to put the framework to use in their own practices, are they welcome to get in touch?

Yes, they are most welcome to get in touch with me. Actually, I would be delighted, because one of the most difficult things about artistic methods or projects is to make them happen without the artist being present.

Finally, do you consider yourself a politically or socially engaged artist? Should artists seek to make the world a better place?

Probably a little bit of both, because my focus in creating scenarios of sociabilities and igniting participants’ (ethical) self-reflections, could become a political arena if the participants wanted to. My work lies in creating ignition and reflection, but I want the participants themselves to take further action. My intention is not to service needs, but to find and name them.

I think art in itself makes the world a better place by sensitizing, provoking or expanding humanity, but I wouldn’t say that artists should be obliged to improve the world.

Instead, it is crucial how art is engaged with (and respected as a very different profession) on a bigger societal scale. The difference to other professions, for example, is that artists do art because they have an inner urge and need to express something that they can’t do elsewhere or elsehow. A society should protect the forms or objects that originate in this deep urge.

After its experience with entartete Kunst during the Nazi rule and the WWII, Germany, for example, realized the importance of art as raising humanity to a higher level and opening Kunstvereins all over the country. Especially in times of populism and the growing right-wing, it is important that art does not become normalized or restricted. After all, it always mirrors the health condition of a society.

So now is the time for artists to go out into and engage with societies that, in turn, should embrace the artists’ abilities to sense tendencies before they become conscious.

1 comment

16 July, 2024 @ 03:48 Teknik Telekomunikasi

What example is given to illustrate changing societal attitudes toward refugees?