How the EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy needs to address its shortcomings to build a future-ready food system.

The European Commission published its “Farm to Fork Strategy” (F2F Strategy) on May 20, 2020, proposing the direction of their plan to restructure the European agricultural systems by 2030. It holds enormous potential to provide the basis for a systemic shift towards a better agricultural system in the EU and set a good example for prosperous economies. Embedded into the European Green Deal, it officially aims to reach the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement, which focus on the drastic reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

The Agreement consists of legally binding commitments and underlying Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that provide flexibility for countries to choose their paths toward reducing GHG emissions. The EU officially ratified the Paris Agreement in 2016. A successful implementation of agricultural reforms would demonstrate the ambition to fulfill the commitments made. A downward shift of the Strategy’s ambitions after scrutiny by the Council of the European Union and Parliament must be expected. Thus, the starting point for the negotiations needs to be set high to ensure that the climate crisis, social issues resulting from climate change, and injustices in the food system are tackled to a satisfying degree.

The EU Commission’s primary tool to implement the F2F Strategy’s elements is the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), a policy framework for agriculture. In 2020, the CAP was renewed for the first time since 2013. Starting now, it will be renewed step by step, in line with the F2F Strategy, with the aim to be in place as a whole by 2030. Recent developments, like the EU Parliament’s vote on the details of the new CAP, which is now a package of tokenistic reforms diluted by economic motives, are warning signals for another period of industrialization and ecological destruction.

Currently, the F2F Strategy is widely criticized by environmental NGOs. Central is the lack of serious plans to transform and reduce the meat and dairy industry. With the livestock sector accounting for about 70% of the EU agricultural sectors’ GHG emissions, it is given surprisingly little attention in the European Commission’s strategy. The Commission proposes to reduce methane and NO2 production in cattle breeding through the usage of food additives, diminishing the emissions by around 18%. While this seems to be a valuable technological achievement, it does not address the underlying issue which is the industrialization of meat and dairy production, and the artificially created high demand for these products. With global production rates in the last 50 years having increased threefold for meat and twofold for milk, to reverse this trend drastic interventions will be needed.

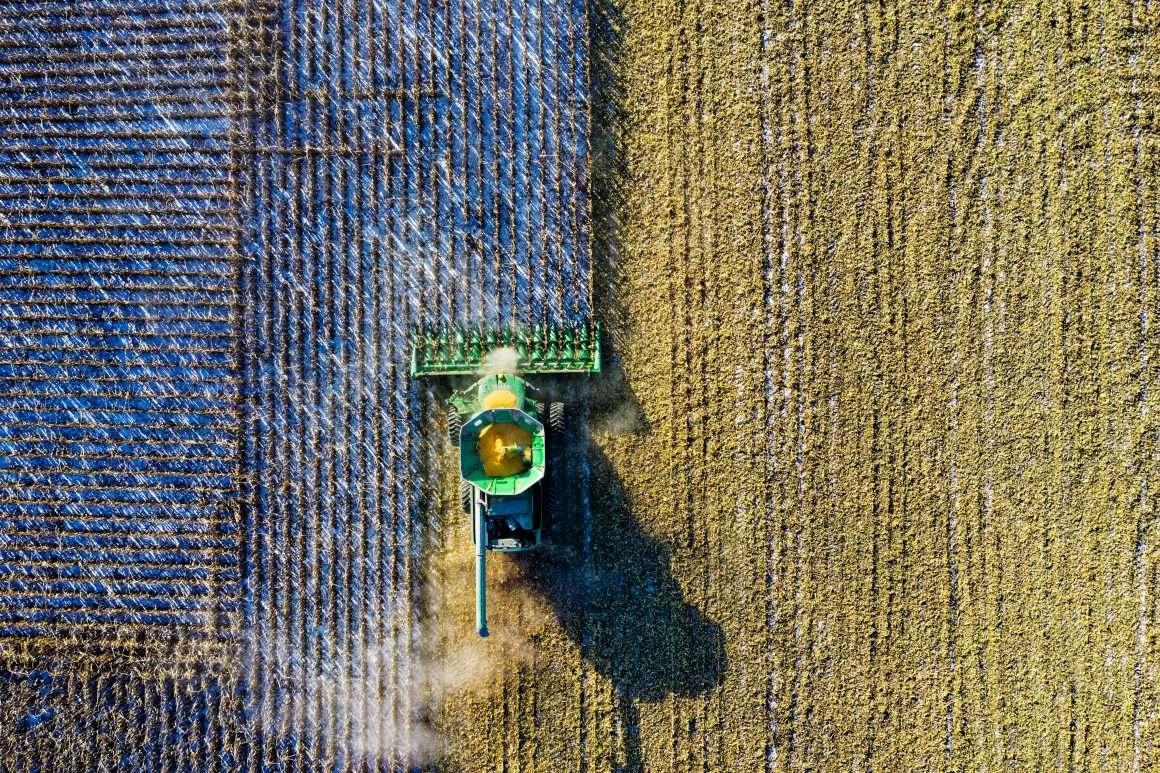

Central in the Strategy is the digital transformation of agriculture. It is presented as a panacea for the whole food system, while, in practice, it may only be a viable solution for large-scale farmers, who can afford the transition to the newest technology. Small-scale farmers and consumers may not profit from digitalization, while the market is on track to become even more skewed in favor of industrialized farming. This is why a multi-faceted regulatory framework is needed to ensure the potential of digitalization will benefit not only large-scale farmers but all stakeholders, from smallholders to consumers to ecosystems.

As a society, we now have to reverse this development and move away from the perception of food as a commodity and towards treating it as a common good

A second European Commission communication paper that accompanies the F2F Strategy is the Analysis of links between CAP Reform and Green Deal. It advocates for more flexibility for producers and national governments, moving away from protectionist ideas towards a more liberal approach. The last decades have brought many valuable policies like guaranteed minimum prices for farm products, setting import tariffs to protect from cheap imported goods, or direct subsidies for farmers’ transition to more sustainable practices. With almost €50 billion in annual subsidies from the European Union, the agricultural sector has proven unsustainable without public support. Moving away from this protectionist path now, handing over responsibility to member states, who have dismantled the environmental EU policies in the last 2 years, could be catastrophic for small and medium-sized farms.

The commodification of food has progressed immensely in the last 200 years. While food was officially declared a human right in 1948, the global agricultural and economic systems have increasingly treated it as a tradeable good. Instead of producing in a way that best meets the demand for food, many countries choose the means that maximize profits. As a society, we now have to reverse this development and move away from the perception of food as a commodity and towards treating it as a common good. The challenge of fulfilling the commitment made in 1948 and working towards a global food system that works for everybody, will become more difficult with soil degradation and the rise of the global population. European agricultural policy developments have the potential to lead the way in the direction of global food security.

The lack of a clear approach to measuring EU member states’ progress during the application of their farming policies and strategies has been met with heavy criticism from leading European environmental NGOs. Even though a “no backsliding” principle is mentioned in the Strategy, to ensure that the member states are working towards the goal of socially and environmentally better working systems, a plan for measuring their success during the process is required. Keeping the flexibility of member states that we see in current reforms is not practical for setting binding sustainability standards and seizing the combined strength of European agriculture. A level playing field and mandatory thresholds have to be set to provide guidelines and real incentives towards sustainable agricultural development throughout the EU.

As the proposed F2F Strategy framework for a sustainable food system is expected to be voted on in the European Parliament in 2023, for implementation until 2030, its success is dependent on multiple complex factors, such as potential shifts in the political climate in the European Union during the next three years. Even if the new policies are not approved by the Council of the European Union or the European Parliament, the Strategy offers a chance to showcase the European ambition and its stance towards fulfilling the Paris Agreement and mitigating climate change.

Going forward, NGOs and political commentators suggest several new approaches that the F2F Strategy should incorporate. First of all, the EU needs to take a more cooperative approach with farmers and workers in the agricultural sector to co-create a sustainable agricultural system. It is crucial to give small-scale farmers a seat at the table to build trust, create incentives, and work out practical plans. To perform a shift towards digitalization, which is a key point in the F2F Strategy, versatile support for small-scale farmers must be made available. This includes financial assistance as well as practical training opportunities, to create clear benefits for the entire sector, not just industrial-size farms. Additionally, serious transformation plans for the meat and dairy sectors need to be added to the Strategy, reflecting their GHG emission share. A clear path towards reducing meat production and consumption is necessary to start a transformation towards more sustainability in the European food industry. Instead of shifting responsibility to the consumer, a system-wide change needs to be fostered by legislation and incentives that support farmers, guarantee the right to healthy food for society as a whole, and protect the environment.