The Conservatives’ sweep to victory in the 7 May general election means that a triumphant David Cameron will be back at 10 Downing Street without much hassle or reliance on a coalition partner to form the next government. The Tories’ 331 seats give him an outright majority, the first of its kind in over two decades. The Labour Party suffered a humiliating defeat and the Liberal Democrats were crushed beyond anybody’s expectation. In response to such a dismal outcome, both Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg stepped down as party leaders, followed by Nigel Farage of the UK Independence Party, another underperformer in this year’s general elections.

This was surely a day to remember, one that brought jubilation to the Scottish National Party, which became literally overnight one of the UK’s major political forces. The SNP recorded a historic landslide victory in Scotland winning 56 of the 59 seats and leaving the Labour Party holding only to one seat. Ed Miliband blamed a “surge of nationalism” for his party’s overwhelming defeat North of the Border.

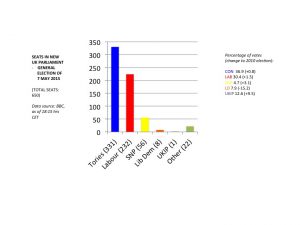

The way this election turned out, we never came to witness UKIP’s burgeoning success at the polls nor the highly anticipated Tory-Labour neck and neck showdown. The scramble for votes gave Cameron’s party a clear win over Labour, which only managed 232 seats out of 650 contested in the House of Commons. David Cameron’s former coalition partners, the Liberal Democrats, won only 8 seats in what is regarded as the party’s worst performance in more than 40 years.

No doubt these elections had a dramatic end, but what is the mechanism that produced this unexpected result? Each of the 650 seats up for grabs in the House of Commons corresponds to a constituency. Whichever candidate gets the relative majority of votes in a constituency, competing for a party or as an independent, gets elected as a Member of Parliament (MP) for that constituency. This electoral system, known as “first past the post”, leaves parties seriously underrepresented in Parliament that may have a significant percentage of the vote nationwide but no relative majority in specific constituencies. This explains why UKIP elected only one MP despite getting 12.6% of the national vote. Some parties choose to stick to specific regions where they have a comparative advantage, as was the case with the Scottish National Party, which fielded candidates only in the constituencies in Scotland.

After their spectacular results, Mr. Cameron’s Tories have enough seats to rule without the help of coalition partners, as was the case for the last five years with the Liberal Democrats. The challenges are no less potent because of that, though. Already in his first statements after his victory, Mr. Cameron showed full awareness of the importance of issues that his government will have to deal with in the next five years, including further devolution for Scotland and other parts of the UK, and the promise to hold a referendum on British membership of the European Union. The repercussions of either of these issues, both for the future of the UK and the EU, cannot be underestimated.