By Georgina Higueras

A reality or just an illusion? The Silk Road is China’s great strategic project and a commitment loaded with opportunities not only for Beijing but also for Europe and other countries. Of course, there are obstacles, especially the instability in Central Asia and the Middle East.

“A heroic mercantile exploit with no prospects”

False. The Silk Road is China’s great strategic commitment as a superpower. In this challenge Beijing combines its internal needs of preserving the stability of its borders and of the western province of Xinjiang; ensures supplies of energy and export markets; developing inland transport routes as an alternative to the risky sea lanes; and reducing the huge differences in wealth between the coastal area and the hinterland. China’s western development policy and its new diplomacy, opening up to the western part of Eurasia, pose a fabulous window of opportunity for Europe.

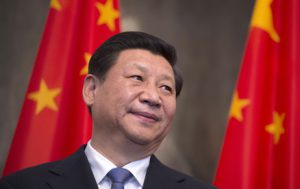

It was in Kazakhstan in September 2013 when the Chinese leader, Xi Jinping, announced his intention to re-launch the camel caravan route which came into being twenty-three centuries ago, bringing the beginning of regular trade between Asia and Europe. In a rousing speech, replete with references to the past and future of East and West, the Chinese president stressed the need to promote the development of their neighbours, which requires the design of a common road network for the transportation of goods and passengers over the mountains and across the deserts and rivers of the Eurasian continent. “About three billion people live in the economic corridor of the Silk Road,” underlined Xi, to draw attention to “the huge existing market.”

A month later, in Jakarta, during a speech in the Indonesian Parliament, the Chinese leader said he not only wanted to create a network of overland connections but also to launch the maritime Silk Road of the 21st century, to link Southeast Asia to the Mediterranean and the coast of Africa through the Middle East, pledging to boost cooperation between Asian and African countries following a win-win principle.

The Silk Road has always been in the political and cultural imagery of China, in whose archaeological excavations of the graves of twenty, ten or five centuries ago we still find sculptures of men with beards and big noses arriving from afar to trade with what was the world’s first economic power until the eighteenth century. It is not surprising that Xi has resorted to this historic route in his efforts to make his dream of the revival of the Middle Kingdom come true. His plan aims to build a whole network of railways, motorways, ports and waterways, plus gas and oil pipelines; mineral mining infrastructure, and information technology with which to continue promoting China’s development.

This is a mammoth challenge due to the instability in both Central Asia and the Middle East. But China, obsessed with continued growth, needs to guarantee the supply of its energy needs and considers the soft power of its millionaire investments to be the best way to achieve this.

“A Chinese equivalent of the Marshall Plan”

Yes, but much more ambitious. Xi’s speeches on the new Silk Road seemed more like a declaration of intent than a project to follow through. However, in a few months it became clear that the initiative was supported by the willingness of Beijing to invest in the plan a substantial part of the four trillion dollars of its reserves. For the time being, the project has been assigned a direct sum of $140bn for infrastructure work, $50bn of which will come from the Asian Development Bank (ADB), recently created by China. The titanic project is taking shape as the Chinese leaders visit the countries of the land and sea routes, leaving behind a trail of millions with those who are enthusiastic about the possibility of the route passing over their land, or offer to extend it with alternative routes.

Some experts see the Chinese Silk Road as a response to the decision by US President, Barack Obama, to “pivot Asia.” The uneasiness felt in Beijing at Washington’s turn towards the East has led to the Chinese pirouette towards the West. The United States has not been able to interpret the importance of the plan until its closest allies, starting with the UK, Australia, Germany, Saudi Arabia and more than fifty other countries, including Spain, rejected his advice not to become members of the ADB, an institution parallel to the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, which is controlled by the US. With the ADB, Beijing will set out its own rules of play for international economic governance, making it clear that its interest is not to challenge US military supremacy in the world, but rather its economic strength.

Washington’s attempt to modulate East Asia by strengthening its alliances and military agreements with Japan, South Korea, Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore and Australia, was well used by Beijing to reposition itself in Central Asia, while US troops began to leave Afghanistan. Similarly, China offered the countries of south-east and southern Asia not only a maritime Silk Road but also a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) with which to rival the US offer of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, known as the TPP, from which China is excluded. The RCEP involves the 10 member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), plus the six with which ASEAN has free trade agreements (China, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia and New Zealand).

“The Silk Road competes against Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union”

This does not seem to be the case. Xi and Putin consider that these are complementary and integrated projects. In Moscow in early May the Chinese and Russian presidents signed an agreement linking the two projects. But while the Silk Road is in full expansion, Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) is going through its darkest hours.

At birth, the EEU was burdened by the crisis in Ukraine, motivated by this country’s doubts over its association with the EU or its joining the Eurasian Union. The annexation of the Crimean peninsula by Russia, after the change of regime in Kiev, sparked condemnation and economic sanctions from the West. In this context of isolation, Moscow has opened up to the Chinese embrace by signing several agreements in various sectors, from military to energy, through financial and cultural, transportation and others. With oil at almost half the budgeted price, Russia desperately needs funding. Beijing, for its part, needs to maintain stable supplies of oil and gas and to modernise its defence in order to continue developing smoothly. This is the basis of cooperation upon which its current leaders are trying to understand each other and are bent on taking measures to strengthen mutual trust and reduce historical misgivings.

Highlighted among the agreements signed is China’s decision to invest $5.8bn on the construction of the Moscow-Kazan high-speed railway, a project of some $21.4bn which will later link up the Russian capital with China through Kazakhstan. This project, which will greatly facilitate the transport of goods and passengers, is one that best reflects the cooperation between the initiative of the Silk Road and the EEU. Once complete, it will reduce the Moscow-Beijing connection to 33 hours, today still a six-and-a-half day trip aboard the Trans-Siberian.

“Central Asia is the scene of Chinese-Russian confrontation”

Not exactly, although both are competing for influence in the region. China posed the recovery of the Silk Road back in the early 90s after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, when it found itself bordering several new states. The urgency of demilitarising common borders and promoting security, stability and understanding between neighbours, however, led Beijing and Moscow to create the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in 1996. China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan were the founding members of the SCO: the only international organization of an almost military nature which includes Beijing. Uzbekistan joined later, and India is in the process.

The economic crisis that plagued Russia, and the need for Beijing to diversify its sources of energy supply, gave impetus to China’s relations with the countries of Central Asia. Furthermore, it is essential for the Asian giant to support the stabilization of these countries. Beijing, unlike the US, is not looking to set up democracies or export their model; what it wants is solid regimes which concentrate on the economy and which do not end in a state of chaos that could affect them. Their priority is to prevent radical Islam from entering the western end of the country, where it already confronts a Uighur separatist group and the unrest of this ethnic group who massively populated the province of Xinjiang in 1949, when the People’s Republic was founded, but which has now been reduced to 43% of its 22 million inhabitants, due to the migration of the Han Chinese (the majority ethnic group in China), imposed by Beijing to control the region.

Obsessed by the fight against the three evils (terrorism, extremism and separatism), the Chinese government intends to make Xinjiang – an area with major reserves of oil and natural gas, also rich in gold, coal and other minerals – the main axis of the Silk Road over land, which splits into two sections in that province: the route which goes through the north of Kaklamakán, towards Kazakhstan and Russia, and the route which borders this inhospitable wilderness to the south, to then continue through Pakistan, Iran and Turkey. Xinjiang will be the biggest beneficiary of the route’s economic corridor.

Last December saw the launch of the high-speed train from Lanzhou (capital of Gansu) to Urumqi (capital of Xinjiang), a project which cost $23bn. China’s pet rail project would link that stretch of high-speed line up with Sofia through Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Iran, Turkey and Bulgaria. Xi Jinping’s strategy for the countries of Central Asia to open their doors to China and allow railway lines to be built, plus the construction of roads and connecting pipelines, is quantified in agreements of $30 billion with Kazakhstan,$15bn for Uzbekistan, $8bn for Turkmenistan and Tajikistan, and $3bn for Kyrgyzstan, one of the poorest countries, the most unstable and the most reluctant to build infrastructures that will give access to “those who come from abroad”.

To give some substance to the western development policy, in 2012 China set up the Lanzhou New Area, a special political and economic district directly dependent on the central government (there are three more on the coast, and Chongqing on the Yangtze River) to promote investment, industrialization and trade. The Lanzhou New Area is the first on the Silk Road but Beijing wants to promote other special economic zones among the countries of the corridor to boost trade and development.

“China’s maritime ambitions spur uneasiness amongst its neighbours”

Yes, that is why Beijing is reaching out to them with the maritime Silk Road, convinced it will bring benefits to all. China, like Taiwan, claims sovereignty over more than 80% of the South China Sea, which covers an approximate area of 3.5 million square kilometres, with numerous uninhabited islands, islets, atolls and reefs, whose sovereignty is disputed between the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Brunei, all ASEAN member countries. This sea is one of the most important waterways in the world, used by most regional trade and for transportation of hydrocarbons. In the case of China the figures rise to 85% of its imports, including 80% of its energy purchases, so in the case of a conflict, this could easily strangle the economy of China; the South China Sea links up the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Border disputes cover five different groups: the Paracel Islands (Xisha in Chinese); the Pratas (Dongsha); the Spratly islands (Nansha); the Macclesfield Islands (Zhongsha) and the Scarborough Islands (Huangyan). To these we could add the dispute between Beijing and Tokyo in the Sea of the Japan over the Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands, which add further instability to the area.

According to China, it delineated its borders in the South China Sea in 1948 using a “nine point line,” which gives its waters a ‘U’ shape, the legitimacy of which was not contested by any country for years. In 1995 there was a first confrontation with the Philippines over the sovereignty of some small islands, although the bilateral relationship was poisoned in 2010 with the arrival of Benigno Aquino III to the Philippine presidency, and the alignment with the United States. Manila went to the International Court of Justice over their differences with Beijing. In Vietnam there have also been riots against China over the Paracel Islands.

In 2002, during the early flowering in their bilateral relations, China and ASEAN signed a document with a code of conduct to be followed by both sides in the South China Sea. ASEAN considers it essential to ensure vital traffic in the area and increasing trade and economic relations. China, however, paid no attention to this until the maritime Silk Road project was underway. In 2013, it again committed itself to promoting mutual trust and good relations with its neighbours in ASEAN, to promote economic cooperation on the basis of mutual benefit.

“The Silk Road runs through a specific number of countries”

No, quite the contrary. China is addressing this as the best representation of its soft power and welcomes with open arms all the governments who wish to join. Last November, Canton held the first exhibition on the maritime Silk Road with representation from 42 countries. One of the most enthusiastic is Pakistan, which was awarded $46bn in investments on a recent trip by Xi Jinping. Pakistan has the dual quality of being an important country for both the overland Silk Road and the sea route. Its flagship project is the expansion of the port of Guadar in the Arabian sea, and the construction of a road across the whole of Pakistan (2,200 kilometres), which would link up the port facility to the Chinese border city of Kashgar. In doing so, China would have an alternative overland route to the Malacca Strait.

The search for alternatives to that insecure Malacca bottleneck is also behind the Chinese effort to win over Myanmar, a country rich in natural resources which is opening the door to the Gulf of Bengal and the Indian Ocean through another friendly country, Bangladesh. Similarly, Beijing wants to put India’s mind at rest and integrate it fully within the new Silk Road, which would slow the Indian slide in the direction of the US. The Asian giant is keen to boost cooperation between the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), its major global commitment, but the border dispute it has with New Delhi and Indian concerns over losing influence in the Indian Ocean limit rapprochement between the two. During the visit in May by the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, China signed agreements to the sum of $22bn.

The overland Silk Road is also gaining adherents. There are now 32 countries that have joined the project, including Spain, which in Madrid last December received the first freight train from the Chinese coastal city of Yiwu in Zhejiang Province. It was the longest railway journey in history: 13,053 kilometres in 21 days, crossing Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Poland, Germany and France. The train was nicknamed The Silk Road of the 21st century and went back loaded mostly with wine and ham. In May this year it made a second journey.

Starting out in the central province of Shaanxi, whose capital today, Xi’An, was founded upon Chang’an, the first capital of the Middle Kingdom and the starting point of the Silk Road, President Xi Jinping believes his initiative brings new opportunities for development for the country and for all those along the route, at the same time as becoming the means to further integration for China within the global economy. Xi advocates a more active foreign policy and, in order that there is no misunderstanding, is in favour of China showing off the muscle which corresponds to it as the second largest economy in the world.

Published by: