The battle over the EU membership within the Conservative Party has exposed the deep-seated divisions as well as contradictions of its Thatcherite ideology. These will outlive the campaign itself.

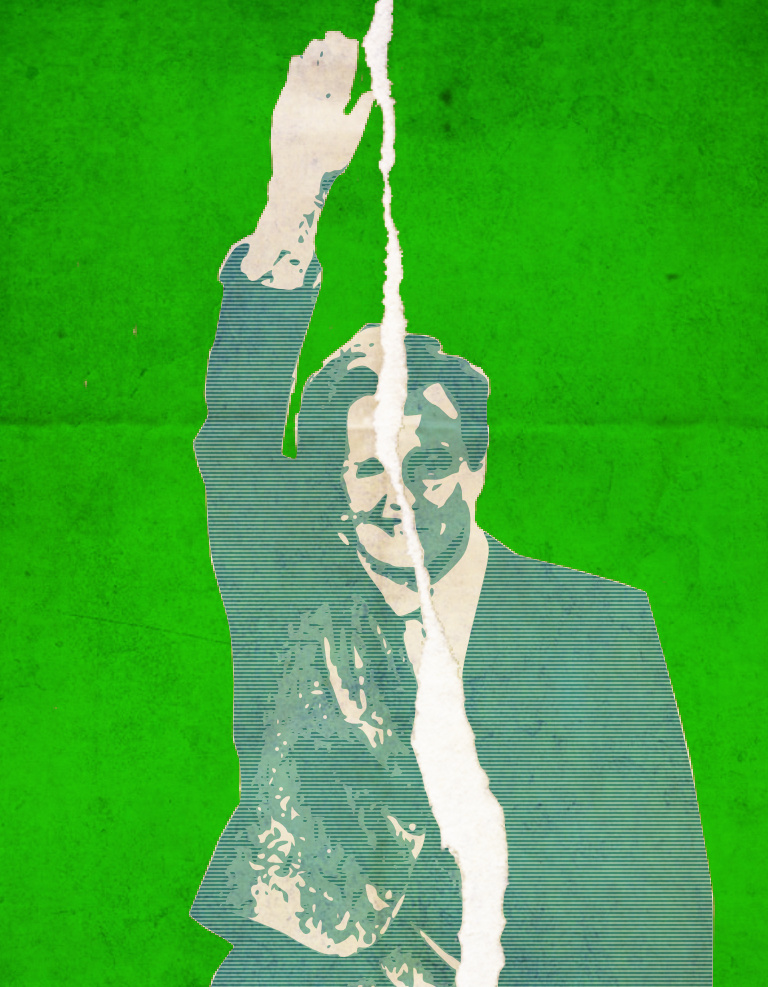

The EU referendum is putting David Cameron’s leadership under pressure in a way in which has not been seen since his election in May 2010. The campaign has led to bitter attacks, sometimes personal, from members of his own government. Prominent Conservatives such as Michael Gove and Boris Johnson, as well as numerous back-bench MPs, wage the ‘leave’ campaign.

This situation has been exacerbated by the resignation of cabinet minister Ian Duncan-Smith (another ‘leave’ supporter) following the recent budget, because of his opposition to cuts in disability allowance. This has caused further criticisms of the Osbourne and Cameron leadership, who seem as isolated within their party as they have ever been since Cameron secured the leadership in 2005. Cameron premiership is ‘finished,’ declared Andrew Bridgsen, a senior Tory MP.

It seems unlikely that party unity could be quickly restored after the referendum regardless of the outcome and a leadership challenge seems inevitable. Hence, Boris Johnson’s election as Prime Minister moves from the realm of fantasy to distinct possibility.

The dissension within the Conservative party strengthens the far-right.

Why is a party which has just secured its first outright election victory since 1992 so keen to overthrow the leader who delivered this victory? But why does the issue of EU membership divide the Conservative party in this way? And will it lead to lasting divisions that threaten the Conservatives electoral position?

In a sense, it is the predictable outcome of the absolute majority that Tories’ currently enjoy in the House of Commons. Cameron has long been disliked by many of his MPs, who tend to be further to the right and more Eurosceptic than he is. They have until now remained loyal, recognising that he is a popular leader who can win the support of swing voters. But after the 2015 election the Conservatives no longer have to make coalition compromises and face no unified or convincing opposition party, with Labour being demoralised and conducting an internal war of its own.

The party discipline is fraying, and the Eurosceptic right has gained in confidence. The fighting over Europe reminds John Major’s premiership during the 1990s, during which rebellions against the Maastricht treaty had eventually led to the formation of the Eurosceptic splinter party UKIP and contributed to the landslide 1997 victory for Tony Blair. The current crisis in the Eurozone and the promise of a referendum on membership has profited the populist right-wingers once again.

The contradictions of Thatcherism as a governing ideology

The main reason for the Tories’ dissension, however, lies in the deeply contradictory tendencies of Thatcherism as their governing ideology. The modern Conservative party is underpinned by two central ideological currents: the ‘one nation’ conservatism characteristic of the post-1945 years, but with historical roots stretching back to Edmund Burke’s critique of the French revolution; and a Thatcherite neoliberalism, which emerged as a response to the crisis of Keynesian post-war economic management and draws inspiration from free market economists such as Friedrich Von Hayek and Milton Friedman.

The first of these is based upon the defence of traditional community institutions, family values and a glorification of the national culture. It is anti-rationalist and pragmatic, preferring gradual reforms based on existing beliefs and institutions to progressive reforms based upon abstract principles.

The second is based on the fusion of radical free market economics and a rhetorical appeal to individualistic entrepreneurship. as well as on a deep belief that the market is the most efficient and rational means of ordering society, and that privatisation along with the liberalisation of labour markets and deregulation will create a competitive and dynamic economy attracting inwards investment.

The Thatcherite tradition still dominates the party. It has been kept in power by appealing to the aspirational lower middle classes, against vested professional interests and welfare claimants. It stresses meritocracy and emphasises the possibility of upwards social mobility for ‘hard working families’ offered by a liberalised and entrepreneurial economy.

Some Thatcherites thus tend to favour remaining in the EU in order to retain access to the single market, boost trade, lower labour costs and enhance competitiveness, while others seek the freedom from the EU regulations to further liberalise the economy and deregulate finance and business. Also, since this ideology is generally committed to a small state, any extra spending on the EU-level bureaucracy is held in suspicion.

The referendum in the context of the neoliberalist policies

However, the Thatcherites’ faith in the market, shared also by Labour’s own Third Way, undermined employment protection and the safety-net offered by social security and the welfare state, and resulted in widespread employment insecurity and the reduction of real wages for most lower middle class workers over the last three decades.

These are the bases of the Conservative Party’s divisions over Europe. On the one hand, Thatcherite pro-business philosophy demands the integrated free markets and cheap labour as well as inward foreign investment, all of which are facilitated by EU membership. On the other hand, Thatcherites must be seen to act upon the effects of such neoliberal free market policies, namely the erosion of wages the disruption of communities and the erosion of national parliamentary democracy.

To square this circle, they increasingly shift the blame for these problems onto migrant communities while stressing the defence of national interests and sovereignty with rhetorical appeals to ‘take back our country’. These counter-vailing pressures cause many Thatcherites to seek Brexit, and to promote the paradoxical vision of a hyper-liberalised and open economy free of the inflexible EU and trading with the dynamic emerging economies, which is nonetheless somehow still sovereign and closed to labour flows.

The battle over EU membership within the Conservative party has exposed some of the central contradictions of Thatcherite politics and will outlive the campaign itself. It might not be the end of Cameron, if he can secure a ‘remain vote’. But the deeper divisions that surfaced within the party will not heal quickly.

This is the second part of a longer article on the UK’s referendum on EU membership. The first part is titled “Brexit Beyond Left and Right: Globalisation, Class and Party Politics in the EU Referendum.”