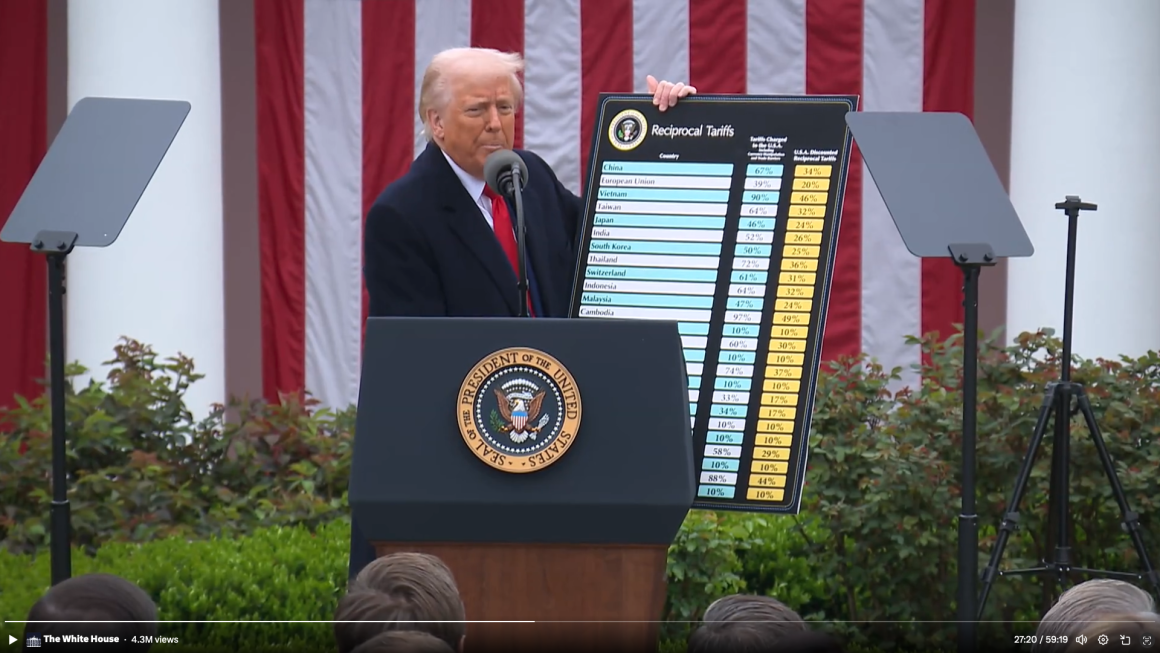

On 2 April 2025, newly declared “Liberation Day for America”, President Trump ceremoniously announced the imposition of trade tariffs on virtually all US trade partners, starting with an across-the-board tariff of 25% on imported automobiles and a minimum of 10% on all other imported goods and services. No favours were done to geopolitical allies and long-time friends of the US, like Canada, Mexico, the UK and the EU. As in the case of China and India, the US tariff calculation for those countries and bloc was based on overt and covert tariffs, taxation, regulation, and currency exchange rate “manipulation” that the other side imposed on goods imported from the US. The stated goal of this major policy shift was to respond to a national economic emergency by allowing local US industries to recover from what the Trump Administration considers unfair competition from around the world, strengthening the domestic production capacity and self-reliance of the US, and eliminating the huge trade deficit that adds to the astronomical debt burden of the country.

One now wonders what will happen next. What the reactions will be from the affected countries and whether this will lead to a generalized trade war, or worse. Countries like the UK and regional conglomerates like the EU and ASEAN may want to try their hand in diplomacy first, in an effort to reach agreement on reduced tariffs, before they reciprocate with higher tariffs from their side too. There is concern that a tit-for-tat response might spin things out of control, which could mean even military confrontation and war. Mercantilist policies in trade helped consolidate major economic powers, not least the US itself, but are also associated with the eruption of major military confrontations, including the two World Wars. If that is the case, the world has taken a(nother) decisive step towards World War III, thanks to the latest US tariff-raising decision that smacks of protectionism.

At least since the end of the Cold War, trade liberalization has been considered by economic orthodoxy as the mainstream win-win paradigm, good for each and every country engaged in it, and the world as a whole. This liberal turned neoliberal doctrine has been punched holes from all sides over the years but had not been seriously questioned in recent decades, not even by the governments of the Global South that seem to be losing out of it. The South’s increasing insistence on South-South and “trilateral” cooperation, including trade, is meant to make the model more beneficial to the Global South economies and to open up developed country markets to tariff-free imports from developing countries. Now, though, the model is being challenged to its core by the country most central to its development, which is also the most coveted market for exports, namely the US.

Is the US drastic turn towards protectionism a necessarily bad thing, though? There may well be another way of looking at it, selfish and unilateral as the original intention may have been. Positive side effects could include, in no particular order:

- Overall reduction in transport for trade, as well as in extreme consumption and waste, which would be good for climate and the environment.

- More reliance of countries of the South and the North on domestic production and diversification of such production to ensure resilience for their peoples. This means self-sufficiency in terms of food products, important medical and para-medical material, energy and raw materials, digital and other infrastructure to the extent possible.

- Reduction of monocultures and raw material supply chains that generally syphon products from the South to the North, leaving behind very little benefit to the country of origin, while exhausting its fertile land and other resources.

- Rethinking of a country’s “comparative advantage”, whether it is considered to consist in low wages and/or cheap resource and/or energy access, often used as justification for the production of cheap goods for the North in the South, actually leading to a low development and “working poor” trap, instead of sustainable development of the developing country/ies concerned.

- Shift of resources and power from a globalized merchant class and North-based corporations that control trade and supply chains to a more democratic and inclusive income distribution among farmers, other producers and merchants around the world.

- Diversifying the currencies used in trade, turning away from the dollar and returning to national currencies or using / launching regional currencies, avoiding undue influence by one powerful actor.

In light of the above, this may well be a chance to redefine globalization, as a qualitative paradigm of getting to know the world, appreciating and benefiting from its diversity of cultures, traditions, languages, foods and artifacts, landscapes and resources, without over-exploiting and eventually destroying it. Unlike the current model of quantitative globalization that focuses on profit and serves primarily the merchant classes and the markets of the North, this would be a much more people- and planet-friendly paradigm that would advance broad resilience and well-being in both the North and the South.