The Union’s critics like to compare it to the Soviet Union. But there is more than an echo of Lenin’s “democratic centralism” in what Mrs May is now proposing.

By Brendan Donnelly

It used to be claimed during the Cold War that in the countries of the Soviet bloc elections could not take place until the government had decided what their result should be. Here in the UK, we order these matters differently. We had a referendum on 23rd June about the European Union, but the government has still to decide what its result will be.

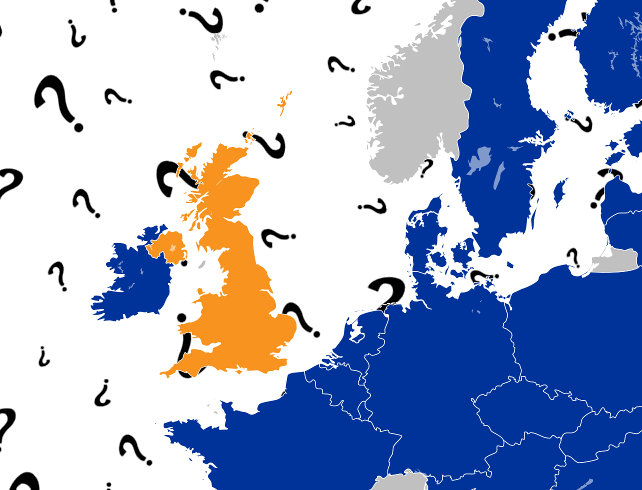

The widely-advertised “brain-storming session” of Mrs May on 31st August has taken us little further in the search for content to fill out the empty assertion that “Brexit means Brexit.” The only specific matter upon which Mrs May and her colleagues could apparently agree was their hostility to the principle of European free movement. This is not an encouraging basis on which to erect a negotiating strategy for the “sensible and orderly departure” of the United Kingdom from the EU that Mrs May says she seeks.

Free movement of labour is a fundamental building-block of the European Union, an element of the sovereignty-pooling which is philosophically at the heart of the Union.

In the weeks since 23rd June, it has become a commonplace to assert that during the referendum campaign Mr. Cameron mishandled the “migration issue.”

It cannot be repeated too often that the free movement of labour is a fundamental building-block of the European Union, an element of the sovereignty-pooling which is philosophically at the heart of the Union. In casting doubt upon this principle, Mr. Cameron was conceding a major intellectual victory to his opponents, a victory only enhanced by his own acquiescence in the lazy use of the term “migrant” to describe very different categories of persons. The Conservative Party Manifesto of 2015 set as a goal the reduction of “net immigration” into the United Kingdom.

This conflation of EU citizens exercising their free right of movement with individuals from outside the European Union wishing to work in the United Kingdom or to seek political asylum allowed “Leave” campaigners to paint a picture of the United Kingdom utterly exposed by its membership of the European Union to uncontrolled (particularly Muslim) migration from the whole world.

Mr. Cameron bears a large portion of the blame for allowing this damaging caricature to take root in the popular imagination. If in the years leading up to the referendum he had used a more reassuring and accurate rhetoric to describe the free movement of EU citizens as a beneficial consequence of the enlargement of the EU always favoured by the British government, his chances of winning the European referendum on 23rd June would have been greatly enhanced.

It is of course generally true that Mr. Cameron’s manifest lack of enthusiasm for the European Union over the past ten years made it more difficult for him to act as a plausible advocate for the “Remain” camp during the referendum campaign. It was perhaps the awareness of the ground that he needed to make up as an apparently passionate convert to the cause of British membership of the Union which led him and the Chancellor to make implausible predictions about the immediacy of economic catastrophe after a vote to leave the EU.

But the tawdry and confused debate on “migration” which scarred the referendum campaign has left a particularly damaging legacy for Mrs May’s government in its attempts to “make a success” of Brexit. This legacy is clearly reflected in the divisions within Mrs May’s Cabinet, not merely in regard to how to “make a success” of Brexit, but even what would count as making a success.

Some of those who voted to leave will have shared Mr. Gove’s view that Albania was an appropriate model for future British dealings with the EU.

Even during the referendum campaign, there were voices raised to point out that the choices offered to the British electorate in the referendum were insufficiently clear, particularly on the “Leave” side. Some of those who voted to leave the Union on 23rd June will have done so in the firm expectation that the UK would continue as a member of the European Economic Area or a similar arrangement; others will have shared Mr. Gove’s view that Albania was an appropriate model for future British dealings with the EU; yet others will simply have voted against what they took to be the shortcomings of the Union with no clear idea of what the alternatives might be. The now apparent divisions within the Conservative Cabinet faithfully mirror these disparities of view.

The government’s interest in popular consultation on European issues is clearly now exhausted. Mrs May has reaffirmed in the strongest possible terms her unwillingness to hold a further referendum on the terms for Brexit or to make these terms the subject of an early general election. It is the Conservative government and nobody else that will decide for what the British electorate voted on 23rd June as an alternative to membership of the European Union. When the Conservative Party has made up its collective mind on that issue, the electorate will in due course be informed.

The high-handedness of the government in this matter could not be better exemplified than by its repeated contention that it is constitutionally entitled to trigger Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty without Parliamentary endorsement for doing so. To use a narrowly won referendum as a pretext for the extension of executive power unaccountable to Parliament calls inevitably to mind Mrs Thatcher’s prescient warning against referendums as a device of dictators and demagogues.

If Mr. Corbyn, as his critics claim, is taking the Labour Party in a Trotskyite direction, there would be a pleasing symmetry in Mrs May’s following Leninist precepts.

It has long been a favoured hyperbole of the Union’s critics to compare its workings to those of such totalitarian regimes as the Soviet Union. But there is more than an echo of Lenin’s “democratic centralism” in what Mrs May is now proposing. Once Lenin’s Bolshevik party had concluded its internal debates, it was the role of the state’s institutions to acquiesce in the Party’s adopted decisions.

The Conservative government seems to have a similar approach to Parliament in regard to Brexit. If Mr. Corbyn, as his critics claim, is taking the Labour Party in a Trotskyite direction, there would be a pleasing symmetry in Mrs May’s following Leninist precepts. It would not be the first instance in politics of making strange bedfellows.

This is an abridged version of Brendan Donnelly’s article first published on his blog.