Spain is accelerating, Germany is slowing down, and Greece is in reverse. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the entire euro area grew by 0.4% in the first quarter, one tenth more than in the last quarter of 2014, according to Eurostat’s first estimate. However, this figure from the EU’s statistics office conceals a disparity in the performance of the different economies in the region.

Low oil prices, the depreciation of the euro against the dollar, and the debt purchase programme, coupled with the low interest rates spurred by the European Central Bank’s (ECB) monetary policy have been the main factor which has benefitted the Eurozone’s economy. But the ECB has warned that the recovery will not be sustainable unless governments work harder with reforms.

Low oil prices, the depreciation of the euro against the dollar, and the debt purchase programme, coupled with the low interest rates spurred by the European Central Bank’s (ECB) monetary policy have been the main factor which has benefitted the Eurozone’s economy.

France and Italy have, without doubt, offset the weakness of Germany: the engine of Europe has slowed to 0.3% from 0.7% last year. The German Federal Statistical Office (Destatis) attributes this growth primarily to domestic demand. Public and private spending has increased and the construction and capital goods sectors have rebounded, but not enough to serve as a counterweight to the export slowdown.

The French economy, which had stagnated in the last three months of 2014, has surprised everyone by growing from January to March by 0.6%, two decimal points more than anticipated by the National Statistics Institute (INSEE). The improvement has been possible thanks to the strong pull from consumption. This is the best figure for the last two years, and could usher in a more sustainable economic resurgence after three years with little growth since President François Hollande came to power in 2012.

Italy has also been a positive surprise. The Italian economy expanded by 0.3% at the start of the year, indicating the exit from recession after falling back by 0.4% over the whole of 2014. According to the Italian Statistics Institute (Istat) increases registered in agriculture and industry and the positive contribution of domestic demand contrasted with the negative figures for external demand.

Spain, which has become Brussels’ laboratory, where austerity measures have been combined with structural reforms, grew 0.9% between January and March – two decimal points up on the previous quarter – and continues to lead among the big countries of the Eurozone.

Recommendations of the European Commission

The conservative government of Mariano Rajoy has liberalized the labour market and restructured the financial system in exchange for the EU bank bailout. But the European Commission is not stopping there, and is now asking Spain to keep turning the screws on the labour market to end moonlighting and the intolerable level of unemployment – over 20% of the workforce – advising productivity-based pay.

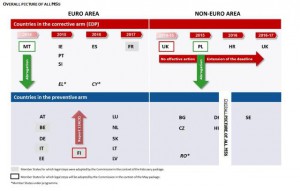

The EU executive also recommends more transparency for Spain in the public accounts of the autonomous communities (self-governing regions) to ensure reducing the deficit below 3% of GDP. Brussels has also sent serious warnings to the UK to reduce its budget imbalance and has announced it will open an excessive deficit procedure against Finland.

“Today we’re asking the member states to ensure that the ongoing economic recovery is more than just a seasonal phenomenon,” said the Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, Pierre Moscovici.

Greece goes back in to recession

The lack of agreement between Greece and its international creditors to unlock bailout funds to avoid suspension of payments has put the Greek economy back into recession, after two successive negative quarters. Its GDP shrank by 0.2% from January to March and 0.4% from October to December, with these figures casting further doubt on the future of Greece in the euro.

The lack of agreement between Greece and its international creditors to unlock bailout funds to avoid suspension of payments has put the Greek economy back into recession.

Last year, Greece managed to come back up to the surface after sinking into the deepest crisis since World War II: six years during which the country has lost a quarter of its GDP and one in four people are out of work. Last week, the European Commission sharply pared its growth forecast for Greece for this year to 0.5% from the previous estimate of 2.5%.

It was the discontent of the population that led the anti-austerity party, Syriza, to power in the January elections but Alexis Tsipras’ government now faces a critical moment of lack of liquidity to meet its financial obligations. Namely, last Tuesday it had to resort to its emergency reserves to cover a payment due in extremis of €750 million to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The Eurogroup and the IMF are demanding that Greece flexiblizes its labour market and reforms its pension system if it wants to continue being financed. The problem is that if it yields to these pressures, the Athens government will openly fail in its election manifesto.

Greece is not the only EU country whose GDP has shrunk in the first quarter. Lithuania (-0.6%) and Estonia (-0.3%) recorded the most negative figures. By contrast, the largest quarterly growth rates were in Cyprus and Romania (+1.6% in both cases).