The referendum has emerged as a way to involve citizens in the decision-making on the European integration. A democratic tool or a deadly threat to the European Union?

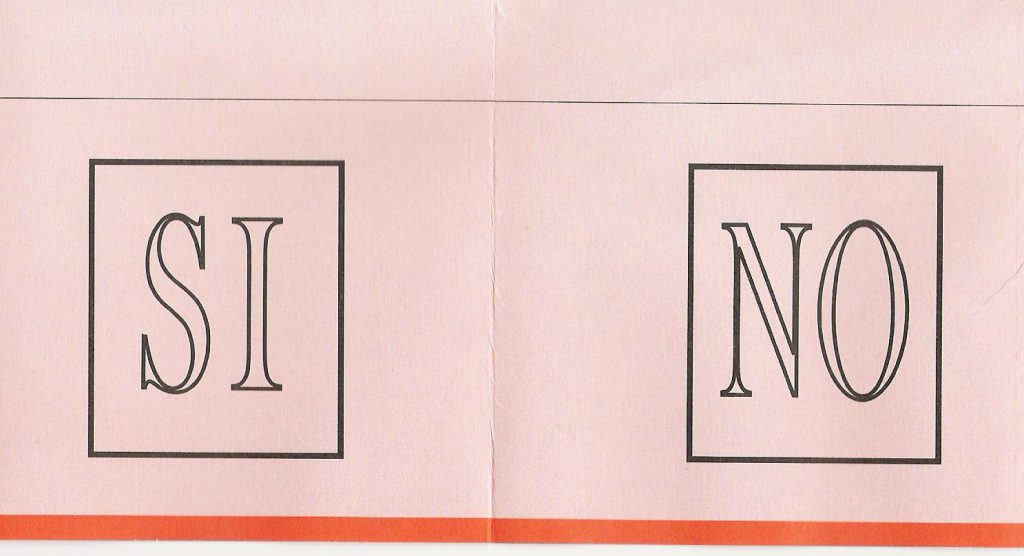

It is widely known that the emergence of the European Community, in the 1950s, constitutes a political step legitimized by prominent decision-makers, but from which the broad public was excluded. This permissive consensus – the art of deciding without the citizens’ consent – ended in the 1970s. By then, new political dimensions emerged. The citizens’ voice expressed through referendums was one of them and people have been asked to give an opinion on several aspects of the European integration process quite regularly. Indeed, from 1972 to 2016, 42 referendums have taken place: 29 favourable to the European Union and 13 against it.

Most of the plebiscites with a positive result for European integration took place in years of Treaty ratification or membership accession. Ireland and Denmark had their positive say on their accession processes in 1972. The Single European Act was endorsed by the Irish and Danish peoples (1986). The Maastricht Treaty was also approved by Irish, French and Danish (the latter went twice to the polls- 1992). In Austria, Sweden and Finland people answered positively to join the European Union (1994). Danish and Irish agreed on ratifying the Amsterdam Treaty (1998), and, later on, in 9 countries, citizens accepted to join the European Union (2003). The European Constitution was sanctioned in Spain and the Luxembourg (2005). The Treaty of Lisbon took the Irish people twice to the polls (2008-2009). The Croatian acknowledged its desire to be part of the European Union in 2012 and the Irish authorized the European Fiscal Compact in the same year. Italy was the only country to hold a referendum to mandate the European Parliament to write a Constitution for Europe before the Maastricht Treaty (1989) and Denmark approved the emergence of a Court to decide on litigations related to European patents- a Unified Patent Court- in 2014.

Nevertheless, there have been less auspicious moments. The Norwegians denied twice to join the European Union in 1972 and 1994. France and the Netherlands dealt a fatal blow to the Constitutional Treaty in 2005. Danes and Swedes refused to join the Eurozone in 2000 and 2003 respectively and, since 2015, all referendums have been hostile to the European Union. Greece refused the bailout conditions imposed by the EU (2015), the Danish denied to convert the opt-out participation in the area of Justice and Home Affairs (2015), the Dutch showed to be against the Ukraine- European Union Association Agreement (2016) and, finally, in 2016, the United Kingdom asked their citizens whether they wanted to remain in the European Union. Actually, this question has only been asked twice: in 1979, to Greenland, and to the United Kingdom in 2016. The majority of people in both countries rejected remaining in the EU.

Should we be worried by peoples’ participation?

But is this democratic tool- the referendum- a deadly threat to the European Union, as many think? Are these surveys a danger to the European project? Should we be worried by peoples’ participation? We shouldn’t, but it might indeed be a deadly weapon.

Throughout times, the issue has raised many speculations and contradictory arguments. On the one hand, there is the general idea that these democratic surveys increment and deepen democracy. On the other, there also is the idea that a referendum is a constraining factor on grounds that negative and less auspicious results might trigger a countervailing momentum. However, peoples’ participation is but the natural impetus that any democratic system should have. And the European Union is a democratic political system.

Since the 1990s, scientists have been proclaiming the sui generis character of the European Union. We can even argue that the European Union already is an unfinished federal political system. Its institutional power configuration and decision-making structure frame the argument and, in this line of reasoning, citizens´ participation in referendums is also an intrinsic part of its democratic framework. Voters make demands, express refusals, and point out apprehensions like in any other democratic political structure. The referendum is but a democratic channel.

In referendums tackling European questions, people express their anger against both national policies and European policies.

In a national state system, parties contest elections trying to convince citizens of their aptitudes. In a national referendum people also express their expectations and policy change requirements directly or indirectly influenced by political parties. However, as far as the European Union is concerned, circumstances take on different proportions. The European Union is an opaque and distant system whose functioning nobody understands, or just a few do. Adding to this, there is a widespread idea that national policies are commanded by the European institutions and people tend to think that Brussels does everything wrong, that most national wrongdoings are but Brussels’ fault. So, in referendums tackling European questions, people express their anger against both national policies and European policies. Perceptions are misleading. The two dimensions are interlinked, interacting in terms of causes and consequences. Challenges, crises and menaces are a profound threat. Peoples are frightened.

Of course, citizens are manipulated. Demagogy, catch-all party politics trying to attract as many people as possible have become part of representative democracy. But the point is, it is much more difficult for any citizen to understand European Union politics and policies than it is to understand their own national political environments. So, it is easier to manipulate and mislead them as far as European Union policies are concerned and some, if not all, national leaders have been doing this for their own political purposes. Of course, there also are the extremist and populist parties exploiting peoples´ fears, weaknesses and illiteracy. Brexit, held on June 2016, is the latest and major example. It is most important, though, to find credible and realistic solutions.

A campaign, a plan, a strategy to explain, to support and galvanize the system are urgently needed.

The European Union is an unfinished project, lacking leadership and ideals. At the moment, the project is facing the most daring difficulties. It faces an economic/austerity challenge, a terrorist solution task and an immigrant’s crisis answer. These gigantic obstacles and the lack of concrete answers have become a huge problem to the European project. Citizens tend to think that the European Union is not able to cope with them. So, it is most urgent that the Union leaders find a way to tell people, to remind citizens, about the good things of the project. A campaign, a plan, a strategy to explain, to support and galvanize the system are urgently needed. Actually, it should already have taken place when Brexit was voted on, if not before (Jacques Delors did that in 1993 when the first dark clouds had started to gather over the European project). Most importantly, it is crucial to listen to peoples’ disappointments, anger and anxieties, bringing hope and enthusiasm to them and reviving the European project.

The United States of Europe needs to be stimulated, needs to be finished, needs to be saved. And with the end of the permissive consensus it is up to each one of us, citizens of the European Union, to do so. A difficult but not impossible task provided the necessary impetus is given.