The organizers of the Paris Peace Forum asked me to convene a meetup to discuss whether globalisation can and, if so, should be rescued. A report

On the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I, President Macron of France and his advisors took the initiative to convene the first Paris Peace Forum (11-13 November 2018). It is supposed to become an annual event that focuses on innovative global governance solutions, as an antidote to the rising tide of unilateralism that is increasingly undermining multilateral cooperation. The fear is that, if the current trend towards populism and combative nationalism continues, the world may witness another Great War, like World War I that marked the demise of the globalisation phase of the late 19th and early 20th century.

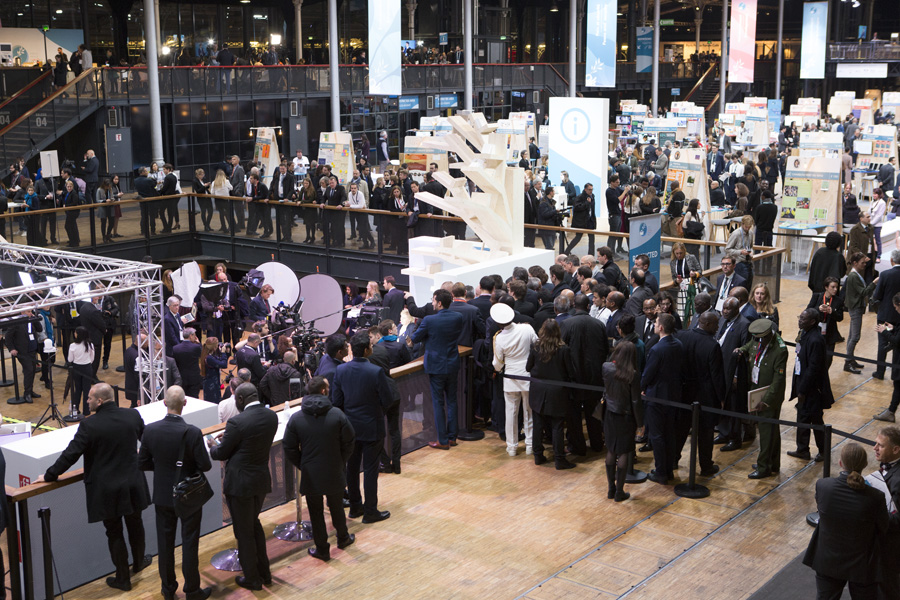

I had the chance to participate in the Forum representing FOGGS. I met several colleagues from think tanks and academia, and from the United Nations, with many of whom I had worked in the past. The world of global affairs professionals is indeed small. But I also met some new people and attended a couple of crowded events with ministers, business people and other celebrities. In a much more modest way, I was asked by the Forum organisers to convene a small “meetup” to discuss the topic of my choice: “Can globalisation be rescued?” In the rest of this article I present the main results of that discussion, enriched with points raised at other events or “in the corridors” of the Forum. I thank all those who talked to me and shared their ideas.

Globalisation has been failing us morally and financially, and it has been failing the environment and democracy. Should anyone shed any tears if it disappears?

So, can globalisation be actually rescued, and if it can, do we really want to rescue it? One can easily see the failures of globalisation as practised in our neo-liberal and, increasingly, also post-liberal world. It is failing morally, with the huge income inequalities that it has generated; the 8 richest people in the world have as many assets as the poorer half of humanity, or about 3.6 billion people, according to Oxfam). It is failing the environment, with the advancing global climate disaster, widely spread pollution, destruction of biodiversity, etc. It is failing democracy, with the rise in populist and authoritarian regimes. And it is even failing financially, most notably in 2008 with the global financial crisis, which is expected to repeat itself sooner rather than later. Why should then anyone shed any tears if globalisation “disappears”?

It is not so simple. Despite its many failures, globalisation has led in recent decades to a previously unseen lifting of people out of poverty and disease, notably in China and India but even Africa. Foreign investment and the resulting rapid industrialisation have created jobs and have improved the infrastructure of these countries, raising the standards of living of hundreds of millions of people. Free trade and cheap transport have brought the world closer together and have made previously “exotic” products readily available around the globe at reasonable prices.

Neither the elites nor the regular people would like to see lost the positive aspects of globalisation.

Neither the elites nor the regular people would like to see lost these positive aspects of globalisation. Despite that, the overall mood at this first Paris Peace Forum was not very optimistic. A lot of energy went into expressing concerns about the future, in view of serious problems identified in the functioning of national political systems, regional integration efforts like the European Union, and international organisations, notably the United Nations. There was a broadly shared view that there is a lack of leadership at all levels, in countries and organisations, which is exacerbating the problems.

With the post-World-War-II liberal global architecture challenged, and with the US clearly declining, despite Mr. Trump’s roaring, it was suggested that China may eventually step in. That, however, was not taken for granted, and the question remained whether, even if that happened, China would (be able to) introduce an alternative model of governance. It was noted that geopolitics is still alive, with claims on territories and resources, and spheres of influence, and could lead to increased tensions and even war. It was actually often remarked at the Forum that leaders at the beginning of the 20th century did not think that a war was possible but they were drugged into it by processes that they had set in motion and at the end realized that they could not control.

Some technological advances seem to do as much harm as they do good for normal people, while generating ever bigger profits for large corporations and powerful individuals.

If one expects a “Deus ex machina” to literally save the world, some technological advances seem to do as much harm as they do good. Instead of improving the lives of people across the board they often lead to more insecurity. Jobs are being lost to robots. Artificial intelligence in driverless cars or medical services makes decisions of life and death for humans. Big data processing seduces consumers and influences the choices of voters. And all this seems done in the service of ever bigger profits for large corporations and powerful individuals, with little attention paid to the needs of normal people and without any sense of common good in mind.

Despite these failings, most discussants believed that the capitalist model would continue to shape global affairs, in some way or other. They favoured, however, a return to a managed system that would work better for all, with robust oversight of the international financial system — the current International Monetary Fund is no match for that — and stricter regulation for companies, including the breaking up of huge conglomerates. Such measures were at the disposal and were actually used by governments in the past, even the US and other capitalist Western countries, before the onslaught on the welfare state that started in the Reagan-Thatcher years.

Some argued that multinationals should be given the right to vote in global governance structures.

That said, for at least one of the discussants, it would make sense to accept that the biggest multinational corporations have assets and influence comparable to those of states, so they should be involved more formally in global governance structures, even with the right to vote, in the hope that would make them more responsible and transparent.

A heartening element in all these discussions was the broad agreement that for the global governance system to improve the engagement of civil society and individuals should be stepped up. To that end, citizen education about the structures and processes of global governance, history taught from many different perspectives and a broader narrative for globalisation and humanity, like the one advocated by FOGGS, should become a priority, especially for young people. There is still hope, but it will take a lot of effort, dedication, good will and broad cooperation to turn things around for the better.