You are Jewish and you are an immigrant and you have an accent and they will never accept you. You will never be one of them.

Dear Dad,

When I was a kid, you pointed out that you and I had the same scar on our foreheads.

“Did you also get it by stumbling while dancing and falling on the sharp corner of a coffee table?” I asked.

“No,” you said. “I got it because a boy in class threw a rock at me because I was Jewish.”

I grew up listening to stories like that about some of the things you went through as a Jew growing up in Soviet Russia.

Kids broke chairs over your head for being Jewish. You couldn’t get into university even though you had the best grades in your class because you were Jewish. My mother, who is not Jewish, was told by an old lady as she was taking my two-year-old self for a walk around the churchyard that she shouldn’t bring me out in public because my “eyes [were] too Jewish”.

I knew your dad abandoned you as a kid and your mom was an alcoholic and that you had to learn early to fight and take care of yourself. I knew you were all alone, and that you carried that bitterness with you into adulthood, and that even when you were married and had a child you still felt alone. I knew that because of the way you would gravitate toward the corners of the room at parties, looking around suspiciously, like even among your own circle of friends you were always waiting for someone to throw a rock.

You worked very hard, working in a factory during the day and playing bass balalaika in restaurants at night. My mother said you did not get more than two hours of sleep for years, and that the bed in the communal apartment in St Petersburg had bed bugs.

She also said that on your first date, you invited her over for spare ribs, but they turned out to be just bones. You still always paid for her cab home, even if it meant you would go hungry.

I respect that — and I respect what you went through.

When I was one, you stopped talking to your mother entirely, because you let her babysit me and she fell asleep on a blanket with the window open in the dead of winter. I remember trying to close the window but being too weak to do it, and trying to pry the blanket from under her stone-cold body, before crying so hysterically that the neighbors had to bust down the door.

A decade later, you wrote your mother a letter in which you said, “No matter what’s happened between us, you will always be my mother.” The letter came back unread. She was not at her address.

You moved to America to start a life for us, working at a gas station. You became the manager of the gas station, then the manager of the parking lot across the street as well. When I was five, you brought me and my mother over. When we entered our Brooklyn apartment, I couldn’t believe how clean it was. I had my own room. It was filled with toys. There was even a television that had several channels. It had never occurred to me that televisions can have so many channels, and this seemed like a symbol of American magic.

I remember watching you anxiously rip open letters about your green card as though they were letters from a lover across the ocean.

You loved America. I remember watching you anxiously rip open letters about your green card as though they were letters from a lover across the ocean. We bought a car, then another, then another. I named the white one Snow White, the red one Little Red Riding Hood, and the black one Black Beauty. We had an apartment with rats, then a larger apartment without rats, then a big, white house on a tree-lined street.

On 9/11, you hung an American flag from the second-floor window that went all the way down to the ground. You shouted “God Bless America!” like any other proud, white, middle-class, American male. You felt like you finally belonged.

I didn’t feel that way. I was the only immigrant in a small private school full of natives and whenever I did anything strange they would call me a “commie bastard” and tell me to “go back to Russia”. When I did go back to Russia, I was told I was that I “betrayed the motherland” and was an “enemy of the people”.

I understood that I did not belong anywhere, that I would forever be an outsider to either of the two countries to which I was supposed to belong, but for some reason that didn’t bother me. I felt like it meant I could find my identity without being muddled by national stereotypes or social pressure, that I could be truly unique. If I didn’t belong to anyone, that meant I only belonged to myself, and that was sometimes lonely but mostly liberating.

On November 8, you voted for Trump.

I am not remotely angry at your for voting for him, although his victory crushed me. I understand that some of your reasons are legitimate. You are a Republican dream, a man who built himself up from nothing, who values overcoming adversity, who believes in hard work instead of payouts, and so align yourself strongly with the Republican party.

You are also wary of the Democratic Party because you come from a country that was destroyed by socialism and you know that it can be a path to hell lined with good intentions. You know big government is bad for small business, which means it’s bad for you. And I understand, though I do not agree with, the fact that you want someone who is going to maintain the world that you want, one in which everyone is straight and successful and has lots of babies.

Like so many Trump voters, you think that putting other people down will make you feel better about yourself.

But what breaks my heart over and over again is your hatred. I cannot stand to be in the same car as you for a single hour because all you do is spill bile everywhere. “Hillary’s a bitch! Obama’s an asshole! Trump’s an idiot! Putin’s is scum of the earth! Look, those fuckers closed the Brooklyn Bridge again!”

When Trump won, you nevertheless proudly changed your profile picture to the Republican elephant and wrote a status that said: “Democrats! Pack up and leave!” That’s such a curious thing to write, dad, not least of all because many of your friends are Democrats.

It’s a tragically interesting psychological phenomenon that oftentimes the same people who were persecuted and ostracized feel the need to persecute and ostracize in return. Like so many Trump voters, you think that putting other people down will make you feel better about yourself, but it won’t.

You dole out insults to everyone who is different from you and yet are enraged and demand apologies if someone insults you in return. You do not listen to anyone. And if you happen to read this article, you will be angry with me for talking about your mother, and you will not attempt to understand what I was trying to say or where I was coming from.

You gravitate toward people who hate you and abuse those who love you. I know it is because you were abandoned and abused as a kid and are now filled with self-loathing. You subconsciously admire those who hate you, because, deep down, you feel you are not worthy of love. This is a very sad thing. And it’s a sad thing I see in a lot of people who voted for Trump.

The thing is, you think that you are a white, American, Republican male, but you are not. Instances of anti-Semitism and hatred toward immigrants have spiked in the days since the man you voted for was elected.

You are Jewish and you are an immigrant and you have an accent and they will never accept you. You will never be one of them. You will never belong.

I love you in spite of everything, and I appreciate everything you’ve done for me, and admire your work ethic and courage. I understand that you’ve had a hard life and are entitled to your anger.

But, for fuck’s sake, you’re almost 60 years old, get some therapy. We live in a country that allows men like you to get therapy. We live in a country that allows for healing. Stop blaming everyone else for your problems — and start getting help.

I’ve told you time and time again that happiness does not come from what everyone around you does. It comes from having a rich inner life.

I do not care if someone calls me a bitch, or tells me I should get raped, which — newsflash! — happens to journalists a lot! I do not care because I know who I am, and I am happy with it, and because of that no one can touch me. This is a very happy thing, in spite of anything that happens politically.

When I was 15, I came downstairs one morning to find you crying on the sofa. “I thought I would have friends here,” you sobbed. “I thought money was all that mattered but it isn’t.”

It still makes my heart ache to think about it, but at the time I hoped that maybe it was a breakthrough moment. It wasn’t.

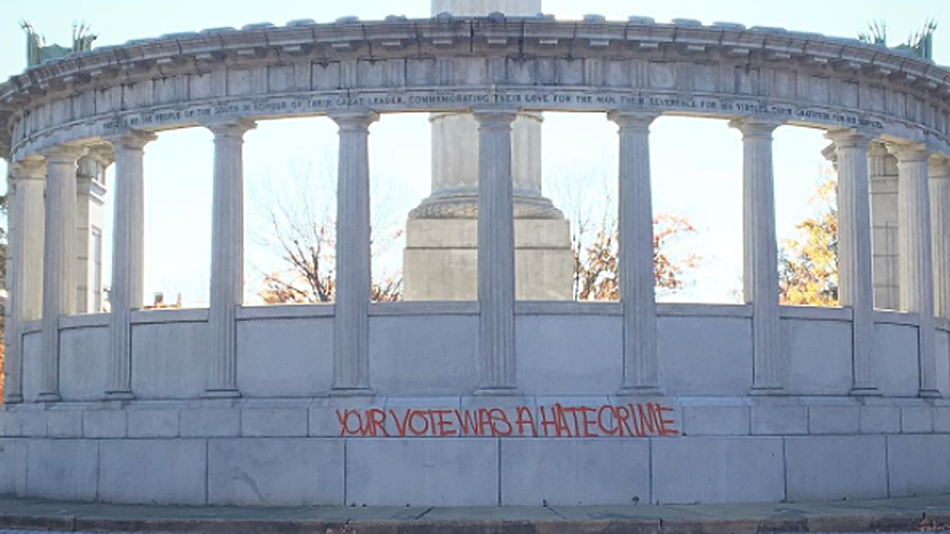

You still throw rocks at people and then wonder why you are all alone. And the America you’ve chosen on November 8 is following the same path.

Sincerely,

Your Loving Daughter

This article was originally published on Open Democracy.