“May you live in interesting times,” says a Chinese curse. Yet, reaching adulthood in “interesting times” might be an even grimmer fate. Jan Gassmann’s documentary Europe, She Loves pays a tribute to European youth’s lost years.

Each year feels historic. We’re used to that by now. Europe’s incessant crises layer one upon the other like archaeological strata. One such layer is the youth unemployment crisis. It has been menacing the future of the continent’s unification project, threatening to turn many current political visions into fossils of extinct hopes.

When the crisis broke out in the media, the youth unemployment in the EU’s peripheral countries such as Greece, Spain and the newest member state, Croatia, was around 50 per cent. There also have been dramatic differences between the centre and the periphery. Only 7 per cent of young Germans are currently unemployed. Against this general background, Jan Gassmann (born 1983) came up with an idea for Europe, She Loves.

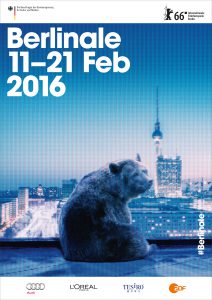

“The idea came to me in the shower,” he says. The film’s première-screening opened the Berlinale’s Panorama Documentary section. Of all places in Europe, Gassmann comes from Switzerland — an island of relative stability in a vortex of EU-crises. “However, even though Switzerland is not a part of the EU, I consider myself European,” said Gassmann during the Q&A. “I portrayed my generation — people who, in a way, missed several years of their lives due to the economic crisis. This film could not have been made elsewhere.”

Gassmann’s team sets out to the four corners of the European Union — Tallinn, Thessaloniki, Seville and Dublin — to film the life of young couples there, to take the pulse of Europe in crisis from its youngest. Gassmann’s cameraman, Ramon Giger (born 1982) follows the life of four couples as they struggle with the unpromising reality around them and fail to dream of a better future, as they make love and do drugs.

In Tallinn, Veronika dances in a Russian nightclub to make ends meet, while, during the day, she struggles to maintain her patchwork family’s cohesion. In Thessaloniki, Penny plans to try her luck in Italy, while her friend Niko seems to have contented himself with his job as a pizza deliverer. Still living with her mother in Sevilla, Caro is refused admission to Master’s studies and puts aside money to move to Barcelona, while her boyfriend Juan can’t really complain after finding a job as a night-shift watchman. In Dublin, Siobhan and Terry make music and fight their drug addiction and hopelessness.

Filming for ten days in each city, Gassmann and Giger gained the full trust of their protagonists. Yet, they also cut the edge of the documentary genre formally. The film’s soundscape is embedded with archival audio-samples, crackling like radio-waves, carrying an ethereal mix of worrisome news, passionate speeches of Brussels’ leading politicians, foreboding analyses of national media pundits, etc. Contrasting this ghostly soundscape with the concrete lives of Europe’s youngest adults is both a test of the reality behind the European idea and a restitution of reality, usurped by the virtual sphere of institutionalized politics and media, back to those lives.

The unabashed sex scenes — made with such a lightness, as if the ban on frontal-male-nudity had never existed — are laboured but also inevitable and almost obsessive. In one such scene, in the thick of it, so to speak, Veronika complains that sex seems to her a replacement for something else. However, the sexuality in Europe, She Loves is not entirely escapist.

Arguably, the very fabric of contemporary existence has been affected by the logic of crisis, which the philosopher Zygmunt Bauman recently described as follows: “Anything can happen, but nothing can be done.” Hence, sex often seems the only feasible possibility to actually do something, to once again make something happen.

“Even the drugs have got boring. Well, sex is still good when you get it,” sings Kate Tempest in her song Europe Is Lost during the film credits. The song could well function as the hymn of Gassmann’s “BoredOfItAll generation” — a generation that is usually called Millennial or “Generation Y” as a reference to the previous post-baby-boom generation that received the letter X. Instead, I would call it “Generation XXX”.

The triple X would allude to this generation’s three crossed-out expectations: of economic participation, of European democratisation and of European unity. It would also refer to the fact that this generation grew up with “live porn streamed to their pre-teens bedrooms.” The film’s visual language is the fruit of porn’s self-evident ubiquitousness, and this fruit is not at all rotten.

Nevertheless, Europe, She Loves is a typical festival-film that is almost predestined not to reach wider audiences. Full of distressing beauty, it is too groundbreaking. Its honesty — at times amusingly insane, at other times unpleasant — makes it a film about which one says: “I’m not sure I liked it, but I truly appreciate having watched it.”

Critics complain that the film is lacking a perceptible thesis. Conservatives see it as an accurate portrayal of contemporary youth — disinterested in politics, killing time with hedonistic and individualistic pursuits, with sex and drugs.

Indeed, the film’s message visual statement dissolves into a dark premonition marked by a lonely figure walking tiredly though dry fields under a cloudy dusk sky scattered with flocks of aimlessly circling black birds. But isn’t precisely this premonition the very aesthetic and political thesis of the film?

“We’re going nowhere, faster than a speeding bullet,” sings Siobhan and strums decisively a minor chord. In these interesting times, new hopes will probably be conceived in the dark.

&

Opening article by Daniel Tkatch

Katoikos.eu exclusive!