With economic stagnation, refugees flocking on the borders, terrorist attacks in major cities and deepening inequalities, people in the EU are increasingly falling prey to populists of the right and the left. Can something still be done to save the European project?

From euphoria to despair

In Paris, 1951, some European countries began an unthinkable adventure: the unification of Europe. 56 years on, in Lisbon (2007) an integrated Union was almost a reality. In the meantime, a single market with free movement of goods, capital, services and people had been developed, a single currency implemented and a governance structure for the European Union had been put in place. Overall, steps in the same direction: a united Europe.

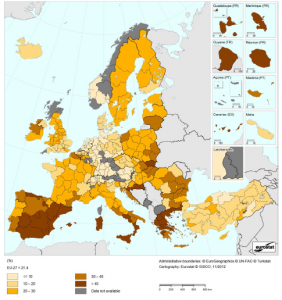

In 2011, however, a major reversal occurred. A pronounced economic and financial crisis took the Union by storm. Youth unemployment reached 23.7% on average in 2013, with Greece and Spain reporting 58.3% and 55.5%, going hand in hand with an incipient negative economic growth of -0.4% and -0.1% in the EU.

But more problems were to come. In 2011, almost 400.00 immigrants came to Europe, and in 2015, according to official numbers from the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) applicants for international protection amounted to 1 392 155, meaning 2676 asylum seekers per million of EU inhabitants.

On top of this, in 2015 and 2016, the heart of Europe was severely attacked by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), and hundreds of people were killed or injured in terrorist attacks in Paris, Brussels, Nice and Berlin.

In the meantime, political groups at the extremes of the left/right divide have gradually been increasing their support, menacing the mainstream of the European party system. So, it seems, the European project is in utter disarray and in agony. But is it falling apart?

A frightened continent

Fear itself can be dangerous. Accompanied by horror and panic, it can induce changes in behaviour and prompt people to react to events irrationally. And there are many sources of fear in Europe. The flood of immigrants and the terrorist attacks are two of them, but unemployment is another one. As a consequence, the psychological landscape of Europe has been transformed and traditional cultural behaviours have been distorted.

In fact, the immigrants’ influx in Europe has revealed a number of serious political fault lines. Initially welcomed by many, refugees were eventually considered an anathema by many governments, which claimed that they could not deal with them logistically, that the newcomers were a threat to national identities or a risk to national security. Measures to prevent immigration (link 1, link 2) went from border controls and the closing of borders to fence building, suspension of ferry links and rail travel, spot checks on cars and even state of emergency declarations with soldiers’ deployment.

As time went by, fear that terrorism would increase in Europe became also part of the refugee rejection arguments. Cases of radicalised asylum seekers, links to terrorism, fraud cases, muggings and violence have been reported. Worst of all, asylum seekers have been the perpetrators of some of the terrorist attacks in Europe.

Those terror incidents were really appalling. In 2016, in 11 extremist occurrences (6 in Germany, 4 in France, 1 in Belgium), 138 people were killed and 548 injured. But what raised more speculation was the fact that the most serious attacks were carried out by Islamists living in Europe, often European citizens themselves.

These problems have had political and social consequences. They deepened an already severe crisis of confidence in the EU and encouraged the emergence of new parties, political and social movements or an unexpected increase in support for others. Indeed, parties at the extremes of the left/right divide have been increasing in popularity, manipulating slogans of fear and hope in programmes that put forward different visions for Europe. Many have been successful, increasing their electoral performance and raising concerns that the traditional European party architecture might change, altering the entire EU political design. But are there serious reasons for alarm?

From the great recession to the far right

Crises always stimulate political change. In times of crisis, governments are reshaped, political movements emerge, and contesting rallying cries take over the political arena. In the European great recession of 2011, it could not be otherwise. So, new political and social movements have been emerging, claiming new approaches to politics, trying to refocus hope and social enthusiasm. The far right has been gaining momentum. The extreme left as well, but not as prominently.

If we look at the 2016 general elections that took place in the EU, we can see a little bit of that. In 2016, there were 9 national and regional elections: Ireland, Slovakia, Scotland, Wales, Spain, the Basque region, Galicia region, Croatia and Romania. Parties in power were all re-elected, but with a decreased number of seats in most cases. Only one won with a full majority – the Basque Nationalist Party in Spain.

Spain’s right-wing Popular Party lost 49 seats, and with them the majority in Parliament. Fine Gael (centre-right) in Ireland lost 26 seats, Direction Social Democracy (centre-left), in Slovakia, lost 34 seats, the Scottish National Party (centre-left) lost 6, and the Labour Party (centre-left) in Wales, one. In Croatia- the Croatian Democratic Union- (centre- right) won 2 seats. In Romania, the Social Democrat Party (centre-left) increased its parliamentary representation by 4 seats. The Basque Nationalist Party also increased by one seat, but Podemos (extreme-left) won 11 seats for the first time. The same in Galicia where En Marea – a coalition of extreme left parties – came second, winning 5 more seats that in the previous election.

Overall, in 2016, elections results show that parties in power lost 131 seats, that some parties came in for the first time and that these were mostly from the far-right.

|

Re-election |

Comments |

|

|

Ireland (26 February 2016) |

Fine Gael- Conservative- Right |

Re-elected. No majority. Losing 26 seats. In coalition with Independents. With the support of Fianna Fáil (liberal, conservative political party) which lost seats. Labour decreased. Sinn Féin (left) increased seats. |

|

Slovakia (5 March 2016) |

Direction-Social-Democracy (SMER-SD) (Social Democrat) |

Re-elected. Losing majority. Losing 34 seats. In coalition with the far-right nationalist Kotleba- People´s Party Our Slovakia in Parliament for the first time and Most- Hid- a centre right party/liberal conservatism |

|

Scotland (5 May 2016) |

Scottish National Party (SNP) – Social Democrat party) |

Re-elected. No majority. Losing 6 seats. The conservatives increased power significantly. Labour decreased it. |

|

Wales (5 May 2016) |

Labour Party (Social Democrat Party) |

Re-elected. No majority. Losing 1 seat. Coalition with the Liberal Democrats. The Conservatives and the Liberals lost power. UKIP – extreme right – won seats (7) for the first time |

|

Spain (26 June 2016) |

Partido Popular (PP) -Conservative, right |

Re-elected. Losing majority. Losing 64 seats (2015), regaining 14 in 2016 (elections took place in 2015 and 2016). The extreme left- Podemos- increased power significantly. |

|

Croatia (11 September 2016) |

Croation Democratic Union (HDZ)- Conservative, right |

Re-elected. No majority. Increasing 2 seats. Coalition with MOST- conservative, liberal- and the representative for national minorities. |

|

Basque Regional Elections- Spain (25 September 2016) |

EAJ/PNV – Basque Nationalist Party |

Re-elected with one more seat. No majority. Podemos, in Parliament for the first time- won 11 seats. All the others lost seats. |

|

Galicia Regional election 2016 |

People´s Party of Galicia- PPdeG |

Re-elected with the same number of votes. Majority. En Marea, the coalition of the extreme left (Podemos and 6 other parties) was second with 5 more seats. All the others (PSOE, Galician Nationalist Bloc and Ciudadanos) lost seats. |

|

Romania 11 December 2016 |

Social Democrat Political Party (PSD) Centre-left |

Re-elected. No majority. Increasing 4 seats. In coalition with ALDE- Centre –right- supported by the right-wing parties- UDRM, PNL, USR, PMP. In Parliament for the first time USR (Union for the Salvation of Romania)- a catch all-syncretic party; the ALDE- Liberal centre-right and the PMP- People´s Movement Party- centre-right |

2016 National and Regional Elections in the EU (source: http://www.parties-and-elections.eu/)

According to the above table, there are two countries or regions registering the emergence of parties of the far-right in their National assemblies or parliaments for the first time in 2016: Kotleba (People’s Party Our Slovakia), whose chairman is considered a neo-nazi, positioned against the euro, and against NATO; and, in Wales, UKIP (United Kingdom Independence Party), a great supporter of the Leave campaign in the Brexit referendum of 2016. In Romania, a catch-all party also emerged for the first time, getting the third place.

Should one be frightened by this trend? What is the general configuration of the far-right parties in the EU at the moment?

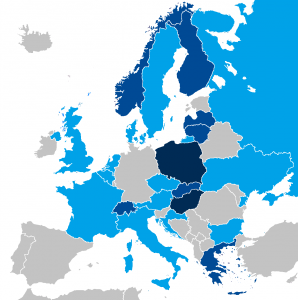

European national parliaments with representatives from right-wing populist parties in 2016. In dark blue, those in government (Source: Wikipedia)

Four parties on the far-right have indeed been gaining momentum in the EU: the FN (National Front) in France, the AfD (Alternative für Deutschland) in Germany, the PVV (the Freedom Party) in the Netherlands, and the FPÖ (the Freedom Party of Austria). There are others with less formal power, at least for the moment, like the Lega Nord in Italy, Vlaams Belang in Belgium, the KNP (Congress of the New Right) in Poland, the UKIP in the UK, and the Golden Dawn in Greece.

Elections are due to take place in some key European countries soon. In 2007, France, the Netherlands and Germany, and in 2008, Austria and Italy. They will be decisive for the future of the EU, as most of these nations are among the founding fathers of the European project.

The FPÖ, in Austria, seems to be the far-right party securing the best results with 40 seats in the National Council, and almost victorious in the 2016 Presidential elections, scoring 46.2% against the Green Party contender, who eventually won with only 53.8%. At the moment, opinion polls suggest that the party might win the 2018 elections with 34%.

The PVV, in the Netherlands, holds 12 seats in the House of Representatives and it is supposed to increase its power, and even win, in the upcoming general elections. The party is leading the polls with 19.3% and 22% of the vote – equivalent to 29 to 33 seats in parliament (link 1, link 2, link 3).

The AfD, in Germany, is also an interesting case study. If in 2013 it was unable to elect representatives for the Bundestag, in 2016, in 5 state elections it managed to elect members in all of them, coming second in Saxony-Anhalt and electing 25 deputies in Berlin where they had never contested before (link). For the 2017 Bundestag elections it is now expected to get between 11% and 13% in support.

The National Front, in France, has also been performing better as time goes by. If in 2012 it only got 2 seats in the National Assembly, in 2014 it won 24 seats for the European Parliament. But the French Presidential elections will soon be held (23 April 2017) and opinion polls suggest that Marine Le Pen, the FN leader, will make it to the second round.

Most of these parties have the same agenda. They want to leave the euro or the EU after a referendum, and they are against immigration. All of them call for more sovereignty to be returned to the national level from Brussels.

The collapse of the Union?

At the moment, the EU does not show the absolutely necessary capacity to reinvent itself for the future. It does not have relevant projects that galvanize ideas, nor major answers to reassure people. Or it has, but they are shy, insufficient, opaque and unconvincing. The economy is stagnant, with forecasts for an annual EU growth rate of only 1.7% for the next years; unemployment is a certainty; the refugee crisis has not been resolved; terrorist attacks are still a threat; and the number of people at risk of poverty have been increasing, reaching 17.3% of the population in 2016. Prospects are thus that the crisis might eventually get worse.

The EU has not been doing enough. Decisions are taken in the grey towers of Brussels, with short briefings to the media, hardly reaching the common citizen. Bad or good, people do not know what Brussels decisions are about, tending to blame the institutions and their bureaucracy for all the wrong-doings and the malaise affecting their national states. And we see no real will and synergies to change the situation. The EU leaders are not giving answers. There is no vision, no credible proposals, no assurances.

As a consequence, people get easily manipulated by the groups at the extremes of the left/right party divide. The far right is steadily rising. From Slovakia to Austria, from the Netherlands to Germany and France (not to mention others), we can see that it is performing better with every election. They might even win elections soon. The far left the same, in the Southern countries.

The citizens’ loyalty is fading away. Out of despair, citizens are reclaiming power, demanding new channels of participation at national, regional and pan-European level, but often with a negative, isolationist agenda, dictated by fear.

Cold winds are blowing from West and East. From the West, the new US President questions the traditional European status quo, from the East, the borders with Russia are seeing a significant arms built-up. Within the EU, Brexit has been menacing the political structure of the Union and domino effects might be expected. The continent of liberty, solidarity and the prevalence of human rights the Europeans have taken for granted for decades is slowly fading away. And nobody is doing enough to defend and restore it.

The EU might not be falling apart right now, but it is struggling with very defiant and powerful forces, against which it is not well equipped. It might not be the end of the EU project just yet, but certainly it is not safe, not secure, not for sure.