As cracks appear in political establishments the world over, Iceland is forging its own path towards an open and inclusive society that puts democracy and its citizens first.

In times of chaos and uncertainty, a glimpse into Iceland could bring hope and inspiration to many outsiders. Following the parliamentary elections, the Icelanders excel with the highest rate of women in politics. Their crusade for transparency is growing stronger, as is their determination to protect whistleblowers. Despite having suffered a financial eruption in 2008, Iceland is thriving and the way it dealt with the crisis is a considerable example to the world.

Parliamentary elections and Pirate fever

Recently, the Icelandic parliamentary elections were brought into the spotlight by the popularity of the anti-establishment Pirate Party, the highest polling party during the election campaign with over 30% of public support. The Pirates were formed in 2012 to promote libertarianism and direct democracy. However, after counting the votes, the black flags gained just 14.5% of the electorate, significantly below the polling projections, but still an impressive achievement when compared to the 5.1% of votes they collected in 2013. With this boost, the recently created party climbed to the third strongest position in the Althing, Iceland’s parliament.

“The good thing about the Pirates is that they are responding to a demand in society for more openness, more transparency and to some extent more accountability and more direct democracy. On all these points I’m very much in agreement with the Pirates’ ideology,” said the Left-Green Movement Icelandic politician Ögmundur Jónasson in an interview for Katoikos.

However, the Pirates’ failure to live up to the projections can likely be attributed to uncertainty over where they sit on the political spectrum and to their vague stance on important matters such as the EU and NATO.

The past months have seen attempts to form a five-party coalition, but the efforts have failed due to disagreements over funding for the health and education systems. But a compromise seems to be on the horizon. According to Reuters, Birgitta Jonsdottír, the leader of the Pirates, was asked by the Icelandic President Gudni Johannensson to continue talks with four other parties represented in parliament, the Left-Greens, Social Democrats, Bright Future and the Reform Party.

Nevertheless, the lack of political stability has not prevented the country from thriving. Iceland’s GDP, already among the highest in the world per capita, is back above the pre-crisis level. Fuelled by a booming tourist industry, the economy is poised to grow by 4% in 2016 and 2017 and unemployment stands at a low 2.9%. Moreover, Iceland is also an attractive destination for investors, with a triple A rating from ratings agency Moody’s.

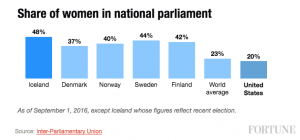

Although a government is yet to emerge, the true winner of Iceland’s recent elections was women’s representation. The volcanic island successfully managed to secure a record number of women in parliament, leading its Nordic peers – Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland – in parliamentary equality, a feat that must not go unnoticed.

The Pirates’ quest to protect whistleblowers

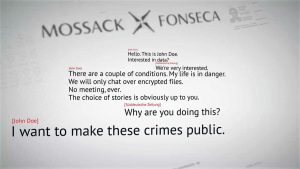

Iceland also stands out for its daring attempt to lead the battle to protect journalists and whistleblowers. The Icelandic Modern Media Initiative (IMMI) is a simple but ambitious project carried out by the Pirate Birgitta Jonsdóttir, which aims to bring together the most progressive media laws from different countries in order to create one comprehensive law. However, for the time being it is a vision that must be further developed. “The good thing about this idea is that we concentrate on the free world, on whistleblowers, on protecting these people,” said Jónasson.

Talking about the core of democracy in a society that is becoming increasingly dominated by trade agreements, Jónasson asked, “Who were the people originally giving us inside information on these behind-closed-doors negotiations? It was Wikileaks who opened up this information that was meant to be secret.” The politician expressed his admiration for Julian Assange’s ideals, saying he “sides with [Assange’s] openness on the secret world of the military and politics”.

As the conversation moved onto the issue of freedom of expression and information secrecy, Jónasson left no doubt as to where his loyalties lie. “I must say if I had to take sides with either Wikileaks or the FBI or the CIA, I would have no difficulty in choosing, I would be on the side of Wikileaks. When we analyse what has happened in recent years and the role played by whistleblowers, we must conclude that we owe them a lot,” the Icelander said.

Rejecting a grim Orwellian future, the Icelandic politician spurned the “moves by many states to increase the security surveillance of their own citizens. I don’t think this is the answer at all.” He insisted on the need for an open society, adding that this kind of surveillance “is what people are revolting against”.

Panama Papers hit Iceland

The Panama Papers triggered Icelandic Prime Minister’s resignation in April 2016. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Ironically, in April 2016 Iceland saw its then Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson resign over the Panama Papers scandal, the biggest leak in history revealing how the rich and powerful use tax havens to hide their wealth. Disregarding national ties, Jónasson said, “This episode definitely falls into the category of good revelations about the political world.”

In fact, Jónasson holds the respectable reputation of being the minister who refused to work with the FBI over suspicions that the “cooperation” was in fact intended to frame Julian Assange, the founder of Wikileaks. “Since they did not have the proper permission from the Icelandic authorities, I immediately broke off all cooperation with them and asked them to leave the country,” he revealed.

Iceland sceptical of the European Union

When searching for a pragmatic solution to the problems facing Europe today, Jónasson came to the conclusion that “the EU has to reconsider its functions very fundamentally”. His major criticism is of the EU’s increasing prioritisation of the free market above social issues. “The emphasis should be changed within the EU. We should be more concerned about inequality and finding ways to make society more equal, to make people feel that this is what we are actually trying to do, that this is our mission, rather than creating a free market,” he said.

As for Icelandic membership of the Union, Jónasson said that his country is not particularly fond of the idea of joining the bloc, as they do not want to give up their fishery rights. But the former minister’s main reason for wanting to stay out of the Union is its ever-growing democratic deficit.

In fact, the reason Iceland was successful in curbing the 2008 financial crisis was in large part down to direct democracy and the fact that its citizens were able to decide on the future of the country in a referendum. This small, glaciar-bound island chose to uphold stability and bring prosperity back to its people, rather than kneel before supranational institutions; a stunt that would surely have been impossible had Iceland been part of the Union.