Many would advise me not to venture into such a minefield as Gaza, literally and figuratively. However, I cannot remain silent in the face of the outpouring of hatred, invective, disinformation and bad faith that distorts and obscures the debate on this issue, which is tragic. I will not engage here in a historical analysis of the problem – apart from a few points of reference – nor will I look for the miracle solution to this crisis, which no State or protagonist will be able to do at this time. I will only try to put things in their proper place and identify ways to redesign the future.

One atrocity does not justify another

But first of all, I want to emphasize my position on the human dimensions of this crisis: one atrocity does not justify another. In other words: Hamas’ atrocities against Jews around the wall encircling Gaza – whether they live on kibbutzim or attend a rave party – are inexcusable. Just as the atrocities committed by the State of Israel and its army — Tsahal — against the civilian populations of the Gaza Strip — whether children, women, the elderly and even the youth, in terms of destruction, death, mutilation and other abuses — are equally inexcusable. There is no justification for these atrocities, which are equally reprehensible on both sides.

However, behind these atrocities lie calculations that can in no way justify them. On the side of Hamas, considered in the Western world as a terrorist movement or, on the contrary, in the Arab-Muslim world, as a movement of resistance, even liberation, the attack of October 7 was clearly intended to strike the minds and relaunch the struggle against those it considers to be occupiers and plunderers: the Jews of the State of Israel. On the side of the Israeli government – now led by the most extremist fringes of the political spectrum – the counter-offensive, officially directed against Hamas but also in fact against the civilian population of Gaza, would have the implicit and unavowed aim of simply erasing the Gaza enclave from Israel’s map and expelling the Palestinians who occupy it. In this sense, the elimination of the Gaza enclave would be the counterpart of the Israeli government’s strategy towards the West Bank, which consists of getting rid of the Palestinian population through the colonization of that space, reducing the latter to confetti on the map of this region, doomed to disappear.

A masked project of ethnic cleansing

Many observers have compared the attack of 7 October 2023 in Israel to that of 11 September 2001 in the United States, because of the element of surprise and horror they both caused. To me, they are more challenging the way in which these events have been politically seized upon to justify reprisals and, beyond that, military interventions. September 11 fell like “blessed bread” for the neoconservatives in the United States, with the aim of justifying and triggering in its wake the military expedition to Afghanistan (2001), followed by the American armed intervention in Iraq (2003). The same was true in my view of the most reactionary, Zionist-oriented government Israel has known since its inception, which no doubt saw the events of October 7 as the perfect opportunity to advance its masked project of ethnic cleansing of Israel. Some even speculate that the Israeli government was aware of Hamas’ plans and “let it happen” to begin its military intervention, as would have done the United States at the highest levels of the executive branch in 2001 in response to reports that a terrorist attack was being prepared. This is implied by the leaks that the Israeli government was warned of the imminence and nature of the “Al-Aqsa Flood”.

What will happen in Gaza in the coming weeks and months? No one knows yet. For the time being, it seems that the goal of the government led by Benjamin Netanyahu, which comes from the Likud but is also populated by extremists of all stripes from the far-right parties and the ultra-Orthodox, wants only one thing: to get rid of Hamas, of course, but also to get rid of the Palestinians in Gaza. The expulsion of the civilian population from Gaza to the south under a deluge of bombs, as well as the implicit eviction of the same population to other areas or countries in the region, are steps in this direction, although the Rafah gate remains locked for the time being for fear of Egypt having to deal with an uncontrollable flood of refugees. In the longer term, the ideas circulating about the future of Gaza would consist of placing this territory under Israeli administration, or even under the administration of the Palestinian Authority or – an insane idea from my point of view – under the tutelage of a third state or a coalition of states, not to mention of course a UN variant, which is not popular at the moment. The fate of the Palestinians in Gaza, as well as the future administration of the territory, remain up in the air for the time being.

Navigating in the fog

The international community is currently navigating in a thick fog, having reacted differently to the events in Gaza. Overall, the so-called Western countries, led by the United States and the European Union, immediately lined up behind Israel, unconditionally condemning Hamas’ bloody attack but turning a blind eye to Israel’s inhumane and disproportionate response. Arab and Muslim countries have also mobilized to condemn the deluge of fire unleashed by Israel on the population of Gaza and to blame once again the policy of double standards practiced by the West. Not surprisingly, the U.S. rushed to send a second aircraft carrier and naval air forces to the area. Unexpectedly, but shockingly, President Macron rushed to Prime Minister Netanyahu to assure him of unwavering support and propose the establishment of an international coalition against Hamas, seriously discrediting the credit that France could still have in the Arab-Muslim world and decades of diplomatic efforts to strengthen its ties with that part of the world. Both President Biden and President Macron then sought to make up for it and save their image by calling on Israel to kill fewer civilians, as if killing civilians at all could simply become normal.

It didn’t take long for the conflict to spill over into the Western and Arab-Muslim worlds. Anxious to prevent political clashes, Western governments have sought to prevent protests and internal reactions, with some, such as France, even going so far as to ban demonstrations in support of Palestine while promoting a broad campaign against anti-Semitism. In the Arab-Muslim world, declarations and demonstrations in support of Gaza and Palestine have multiplied, as was to be expected. Not surprisingly, too, anti-Semitism has entered the debate, driven by Jewish pressure groups and lobbies and with the complicity of governments close to Israel. The waving of the Holocaust ghost and the denunciation of anti-Semitism — the supreme accusation to silence and nip in the bud any criticism of Israel — has resurfaced aggressively.

A new threat for the Middle East

At the international level, the conflict resulting from this new crisis threatens to engulf the Middle East and even beyond. The protagonists likely to intervene against Israel if the crisis worsens are known: Hezbollah in Lebanon, Shiite militias in Syria and Iraq, and even the Houthis in Yemen, for the moment in a limited way and as a proxy on behalf of Iran. The so far anecdotal seizure of Israeli-owned cargo ships in the Red Sea, as well as the launch of missiles towads Israel by the Houthis, suggest the possible extension of the conflict. States such as the United States and France immediately understood this by sending naval air forces to the region. Attempts at mediation have also multiplied in an anarchic manner on the margins of the United Nations, without success apart from the release of a handful of hostages and a few days of truce in the Gaza Strip, a worrying sign of a retreat in multilateral diplomacy.

Finally, with regard to the United Nations, there has been a worrying decline in its role in peacekeeping, as a result of the paralysis of its Security Council and the attacks on the Organization. This has manifested itself recently with the war in Ukraine, which pits the permanent members of the Security Council against each other, in addition to the misuse by some of them of their “right of veto”. This decline has been accentuated recently with the trend towards the multiplication of separate meetings of groups of states (i.e. the G7, the G20, the BRICS, etc.) and international forums held on the margins of the Organization, as well as attempts at mediation between States conducted outside the Organization. Added to this are the malicious or rather ill-intentioned criticisms of the United Nations, including the systematic denigration of the United Nations by one of its members, the State of Israel, which not only systematically violates its resolutions, but does so with the blessing and veto of the United States. Added to this is the insolence of Israeli leaders when they declare, among other things, “lecturing” the UN (sic) through their permanent representative to the Organization or when, without fear of ridicule, they accuse UNIFEM (UN Women) of complicity with Hamas for its alleged silence in the face of sexual violence committed against women during the October 7 attack. Fortunately, the role of the United Nations is far from limited to peacekeeping at a time of climate change and the multiple dangers that threaten the planet, ranging from human misery to pandemics, not to mention the countless tensions and imbalances that threaten our world.

Getting out of the Gaza crisis

How can we get out of the Gaza crisis and, beyond that, this never-ending confrontation between two peoples, the Jewish people and the Palestinian people? Few analysts are currently venturing down this particularly thorny but oh-so-necessary track! In the very short term, it is obvious, there should be a ceasefire. Let’s call it “humanitarian” if you like, or whatever. Only strong pressure on Israel, from its supporters, led by the United States, is likely to achieve this result, at the cost otherwise of a humanitarian disaster and a new “Nakba” with dramatic consequences (the “catastrophe” of 1948 in the Palestinian historical narrative).

Secondly, a formula of administration should be quickly put in place in this battered territory for the survival of its population and for its eventual recovery. Let us reject from the outset the outright annexation of this territory by Israel, accompanied by the expulsion of the Gazan population, which is politically and morally unacceptable. Direct administration of this territory by Israel would theoretically be conceivable, but at the cost of a ferocious repression of the people of Gaza that will never forgive the horrors committed by the occupier. Hamas’ continued administration of Gaza would also be theoretically conceivable, but intolerable in the eyes of Israel, which has vowed its destruction. An administration of the Gaza Strip by the Palestinian Authority is also on people’s minds, but it would suffer from all the ills that affect this Authority, on a larger scale in the space where it is confined: political, economic and security submission to the State of Israel, which in fact occupies and administers this fiction of a Palestinian State. As for the mandate that could be assigned to another State or a group of States, it would lead to an unstainable mode of management or co-management in view of the complexity of the case. The only viable solution remains: to hand over the provisional administration of Gaza to the United Nations, which knows the territory well, has worked on it through UNRWA for 74 years and enjoys the confidence of its people. The establishment of such an administration would not be new to the Organization, which had successfully implemented it in the past, including in East Timor, during its reconstruction.

Thirdly, in the longer term, there would remain the question of peaceful coexistence between the Jewish and Palestinian peoples, who have been at odds since 1948. The Middle Eastern model of communal coexistence between populations of different faiths (Lebanon and Syria in particular) has often been mentioned, but its practical functioning in the region leaves much to be desired in view of the successive crises experienced by the States concerned. The solution of a multi-confessional and multi-ethnic state seems attractive and has long been on people’s minds, but it turns out to be utopian in the real world given the outpouring of hatred and resentment that has accumulated on both sides since the birth of the State of Israel. Palestinians of Israeli nationality live and work in Israel, but their status as citizens seems increasingly precarious in the context of the violence and resentment that is developing in the country. Progressive Jews and local NGOs are campaigning for a rapprochement between the communities, but their struggle seems doomed to failure in the climate of animosity and horror that prevails today and is unlikely to be resolved overnight. This leaves the two-state solution, the only viable long-term solution for peaceful and – why not? Let’s dream it – friendly coexistence between the two peoples.

Revisiting the two-state solution

The two-state solution has been tried and failed, many observers and protagonists will say. But it failed because it was built on shaky foundations and systematically undermined by its opponents. Brought to the baptismal font in Oslo (Oslo Accords, 1993-1995), it provided for the gradual establishment of a sovereign Palestinian entity but subsequently only resulted in an ersatz state, subject to the goodwill of Israel. It will take too long to list here the shortcomings and even violations of the Oslo Accords, ranging from the military occupation of the West Bank, the colonisation of its land by Jewish settlers, the expropriation of the Palestinians of East Jerusalem to the trusteeship of the Palestinian Authority in the context of economic, financial and commercial agreements that restrict it. Not to mention the security and military control of the entire Palestinian population. Some have compared today’s Palestine to a Bantustan, others speak of apartheid to characterize the system in place or a ghetto to depict the situation in Gaza. The proto-state called the “Palestinian Authority” is not sustainable, let’s put it bluntly. Only a contiguous Palestinian state, stretching from the West Bank to the sea and fully sovereign, would have a chance of being viable and thus contributing to the lasting healing of relations between the Jewish and Palestinian communities.

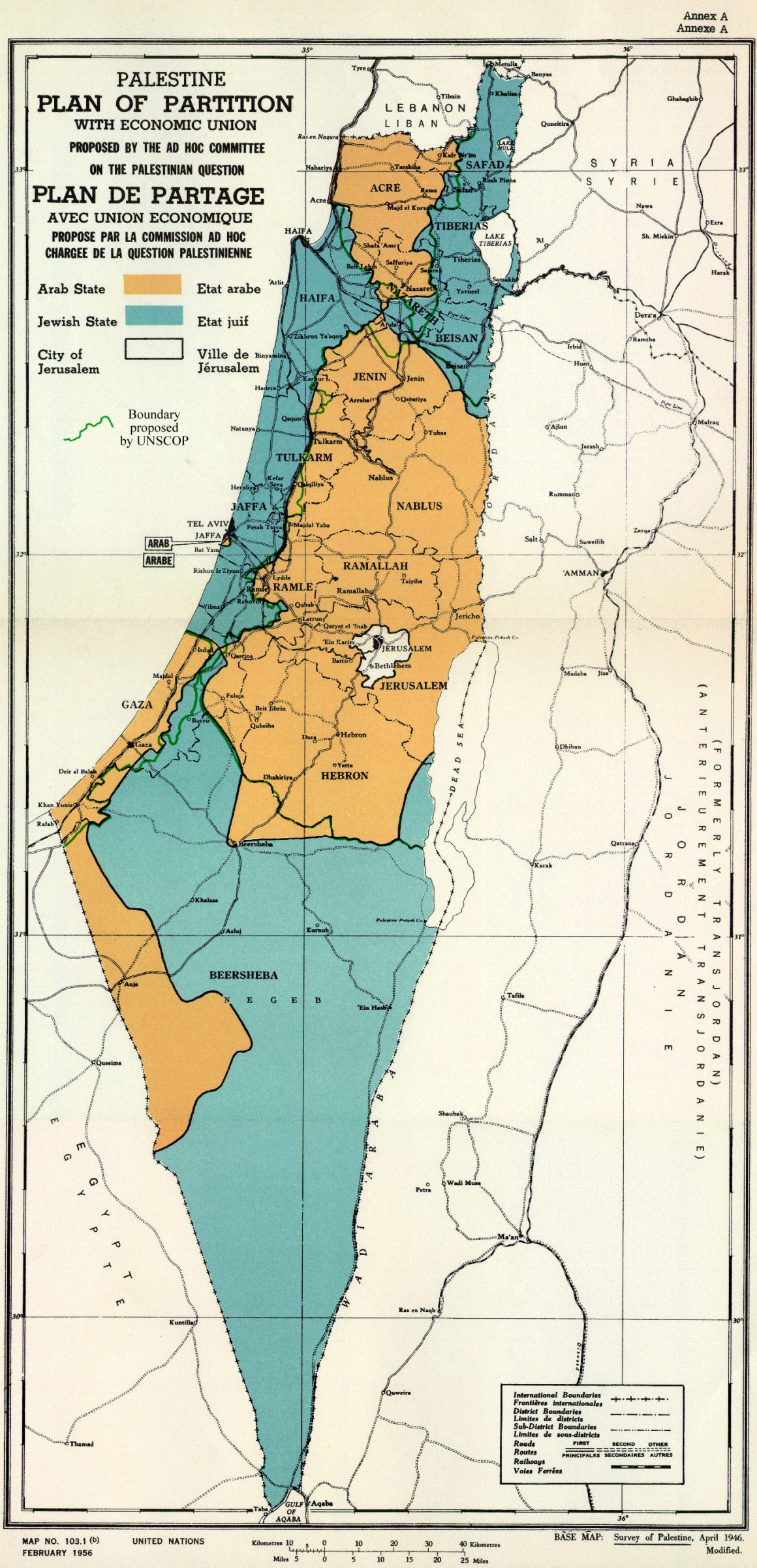

Building a contiguous and fully sovereign Palestinian State requires mutual concessions that go far beyond the Oslo Accords. This would require mutual land cessions and agreements on the status and compensation of populations affected by transfers of sovereignty. This could take the form, among other things, of a cession to the future Palestinian state of the north-west of supposedly Israeli territory, in exchange for the cession to Israel of the Gaza Strip and part of the West Bank. The “Northern District” of Israel, attributed mainly to the Arabs in the partition plan for Palestine (approved by the UN in 1947) would thus be retroceded to the new Palestinian state, giving it continuity, depth and access to the sea, while the Golan Heights, annexed by Israel, would be retroceded to Syria. Israel would gain compensation from the Gaza Strip and part of the southern and even western West Bank. Israel would thus gain continuity, depth and security, no longer having borders with Syria and Lebanon. Jerusalem, ideally, should regain its international status, subject to co-management of the city by Israelis and Palestinians.

A new generation of leaders

Negotiating such an agreement would first require a new generation of leaders to come to the negotiating table and overcome the hatreds and resentments of the past. Obviously, time and patience, as well as calming measures, would be needed to move gradually towards such a goal. This would necessarily imply a political transition between generations that could pave the way for such changes. On the Palestinian side, Fatah and Hamas would agree on a new political platform for the future of Palestine. The release of currently imprisoned Palestinian leaders could also, according to many observers, be a game-changer, if Israel’s leaders have the intelligence to do so. A similar process would also be desirable on the Israeli side. Once the trauma of the October 7 attacks has passed, a new generation of leaders should take the lead in courageously addressing the root causes of the conflict and finding a modus vivendi between the two peoples. The United Nations, for its part, could support this process, with a low profile, by quietly but effectively promoting dialogue between the parties in the form of discussion forums and informal meetings between actors on both sides, in the hope that solutions for the future will emerge. It certainly wouldn’t be for tomorrow. But this would be the only politically conceivable way to overcome a confrontation between two peoples that has lasted far too long, generating blood and despair from one generation to the next.