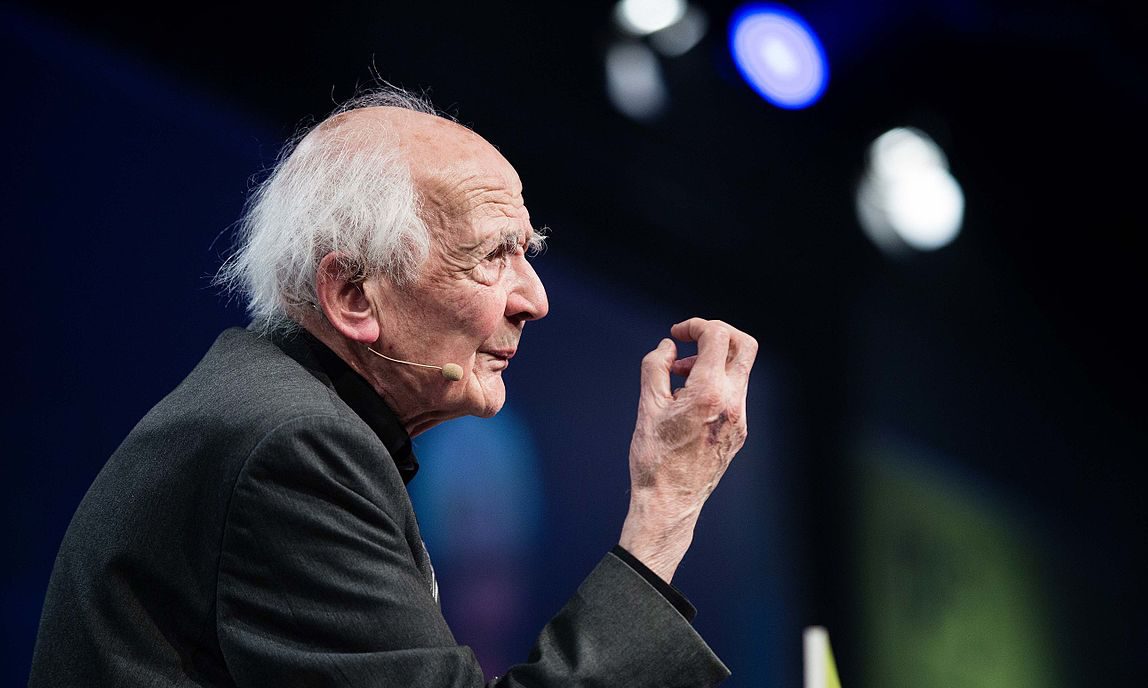

Zygmunt Bauman was a consistent critic of postmodernity and identified the basic mechanism of reproduction in contemporary societies: consumption and seduction.

We have accustomed ourselves to treating Zygmunt Bauman’s work as a process. Taking into our hands his consecutive books, we were wondering what insight into modernity he will offer this time, how did his thinking evolve, and how does it relate to his previous thesis.

Today, with great sadness, we have to accommodate the thought that Bauman’s life and work has achieved its definite form.

Bauman’s work has always been defined by intellectual courage and audacity. Whether he was writing about the sociology of knowledge in 1960s or about consumption in the 1990s, he always related his analysis to the great themes of social thought: emancipation and alienation, autonomy and domination, identity and otherness.

The importance of his books came from his ability to combine sensitivity and focus on concrete things with a talent for building big narratives about freedom, modernity and hopes for gaining control over reality. When one adds to that his lucid and beautiful language, it’s easy to understand why not only was he a renowned academic but also a popular writer to whom people turned for explanation of how their individual problems connect with collective fate.

For me, three things settle the issue of Bauman’s uniqueness in contemporary thought. First, it’s his reflection upon the unintended consequences of social projects. Second, it’s his analysis of postmodernity as a system of exclusions and third, his attempt at founding an ethics of “nonavoidance”.

As the author of Modernity and the Holocaust or Legislators and Interpreters, he studied how hopes for establishing an ideal social order can turn into a system of violence and domination, which eliminates people who are dangerous for that order or who remind that the world is not perfect yet. Today, his diagnosis that the pursuit of some final ordering of reality often leads only to more and more chaos, ambiguity and uncertainty that give birth to a vicious cycle of frustration and aggression, seems to be unusually correct.

Although the author of Legislators and Interpreters had the label of a postmodern thinker and many thought of his work as affirming modernity as a fulfilled utopia of individualist choice, similar to that found in the work of Anthony Giddens, one has to remember that Bauman was a consistent critic of postmodernity.

He noticed that the basic mechanism of reproduction in contemporary societies is consumption and seduction, and not ideology and sanctions, but that at the same time the system produces social exclusion and domination. The homeless, the poor, the “flawed consumers”, the refugees, the illegal migrants: Bauman gave a place in public debate to the outcasts of postmodern times, the people uprooted from their communities by global capitalism and pestered people’s conscience by showing them that their individual welfare has its dark side and a price paid by other people.

Zygmunt Bauman was aware of the limitations of traditional ethics of rules and remained wary of grandiose projects of enforcing them on people.

At the same time, he never was a nihilist or a supporter of leaving things to divine providence. He searched for an ethics that would allow for standing up to injustice without leaving a trail of fire. First, he sought inspiration in Emmanuel Levinas’ principle of responsibility for the Other – a concrete and alive person who embodies ethical challenge. Second, as Adam Ostolski once said – he practised an ethics of not turning a blind eye to the world.

It’s often said that as long as one’s books are read or even as long as one’s ideas have influence upon people’s minds, one exists even after death. Bauman’s books preserve his sensitivity and wisdom and his work won’t be exhausted as a source of concerns and illuminations any time soon.

Maciej Gdula is a professor of sociology at University of Warsaw and a member of Krytyka Polityczna, a circle of Polish left-wing intellectuals gathered around a journal of the same title.

This article is co-published with PoliticalCritique.org.

![]()