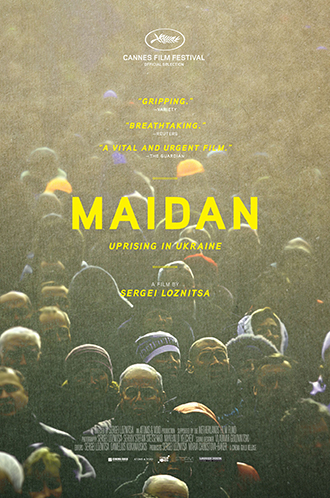

As NATO and Russian forces increase the size and frequency of their military exercises at the eastern boarder of the European Union, between the momentary disappearance of Vladimir Putin from the surface of the world and the one-year anniversary of the reattachment of Crimea to Russia, Sergei Loznitsa’s Maidan is a soothing break from the crisis situation in Ukraine.

The 17th project of the Ukrainian director, which was selected for the Cannes’ Film Festival, does deal with Ukraine, though, and more precisely with the Maidan revolution, which toppled former President Yanukovych. However, it does so without enunciating a single word, just bringing together fragments of this revolution, from the peaceful rallies to the bloody street battles, which caused more than a hundred deaths.

Sergei Loznitsa mingled early with the people of Maidan, the central square of Kyiv that gave its name to the revolution and the documentary. His camera follows the constant evolution of the movement, almost exclusively using fixed shots, conveying both individual and crowd-size reactions and emotions, and giving the true impression of being an invisible observer of the revolution.

Going through winter 2013/2014, a few specific moments stick to memory: the huge tire fires that burnt without fading on the barricades of the square; the human chains focused on bringing cobbles to the front lines of the street fights with the state riot police, or simply the volunteers worried about bringing enough food to the many Ukrainians gathered on the square during the early days of the uprising.

Maidan is deeply infused by Ukrainian culture and, to some extent, nationalism. Various scenes show priests preaching from the platform standing in the middle of the square, other scenes show the national anthem being sung by demonstrators. Maidan does not meddle with geopolitical analysis and Mr. Loznitsa explains himself: “Maidan is a portrait of an awakening nation, rediscovering its identity.”

Cold, factual analysis was never the aim of this movie and therefore it should not be perceived as such, but cold factual analysis of the Ukrainian crisis is scarce even in Western newspapers. The true value of Maidan, along with its artistic beauty, is that it offers a Ukrainian take on the Ukrainian revolution, and it does not go further.

Towards the end, one is gripped by emotion as the documentary shows the funerals held on the square for the persons who fought and died in the uprising. The angle chosen by Sergei Loznitsa makes one feel a part of the chanting and mourning crowd.

Esta publicación también está disponible en: Inglés