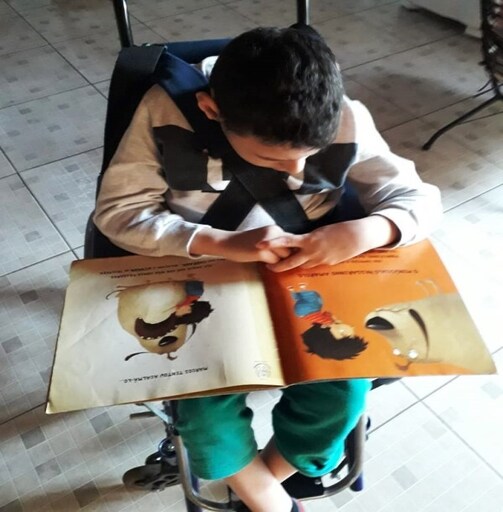

“I feel the pandemic has highlighted the invisibility of people with disabilities,” said the mother of Luigi Gabriel, a 9-year-old boy with cerebral palsy. Throughout history, it has been proven that the most vulnerable groups are mainly affected, in many ways, by the risks related to humanitarian crises. The most recent example is the pandemic of the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), which has highlighted a number of outstanding challenges at a global level.

In Latin America, where persons with disabilities (PWDs) represent around 13% of the population, disability is a complex issue with wide social and economic repercussions, mostly due to the lack of reliable data. Statistics are scarce, outdated, and inaccurate. Therefore, the work on disability-related policies or programs is based on estimated data which is, at times, quite far from the countries’ reality.

One in seven people in the world has a disability, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). In Latin America and the Caribbean, the last censuses in 2010 report disability rates ranging from 5.1% in Mexico to 23.9% in Brazil, while in the Caribbean the rates range from 2.9% in the Bahamas to 6,9% in Aruba. Approximately 66 million people in Latin America are considered to live with at least one disability, according to figures collected from different statistical sources in the region, which are not always comparable with each other.

Based on the social model of disability, the way we think about and measure disability has changed in recent decades. Measuring the prevalence of disability involves including questions in surveys that are representative of the population of interest. PWDs constitute a minority in society, not so much because of their relatively small numbers but because they occupy unequal spaces in the exercise of their rights and in their (lack of) access to opportunities due to their invisibility in the social environment.

In a pandemic and social isolation scenario, the need for care and support from third parties in routine tasks are challenges that exceed the obstacles already experienced by this portion of the population.

Regarding the legal guarantees of PWD rights, in 1976, the UN General Assembly passed United Nations Resolution 31/123 which proclaimed 1981 as the International Year of Disabled Persons (IYDP). The UN resolution 31/123 recognized the responsibility of states to guarantee equal rights to people with disabilities and set out a democratic framework of social, structural, and political changes to address the issue within the sphere of human rights. However, it would be another 25 years before the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – the main document that recognizes and guarantees the rights of this minority – was finally adopted by the UN, on 13 December 2006; it entered into force on 3 May 2008.

Despite the legislation and the social inclusion initiatives already implemented, people with disabilities continue to experience difficulties in accessing their fundamental rights. As a result, the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic are more pronounced for them. In a pandemic and social isolation scenario, the need for care and support from third parties in routine tasks are challenges that exceed the obstacles already experienced by this portion of the population. In Brazil, for instance, some of the challenges include public transportation, health assistance, the development of socio-economic policies to help families during the quarantine, and so on.

The risks are so apparent that they motivated the UN to launch a worldwide appeal for people with disabilities to be included in recovery and crisis response actions. In this appeal, the UN Secretary-General António Guterres stressed that PWDs suffer from a lack of accessible information on public health and struggle against significant barriers to implementing necessary hygiene measures and accessing health facilities. The Secretary-General also highlighted that this group is more likely to live in poverty and suffer higher rates of violence, neglect and abuse, emphasizing that the pandemic intensifies these inequalities and produces new threats.

The risks and challenges mentioned are not limited to the public health agenda but may have more widespread implications. How can PWDs work, study or engage with society during a crisis if they are a high-risk group? The Communication Professor and Doctor in Public Health, Cilene Victor, points out that in the 1980s the first studies in the field of risk communication recognized its potential to promote horizontal, transparent and, therefore, more effective decision-making by identifying the various social actors directly and indirectly affected.

There is an imminent need to advance quantitative and qualitative research on how visible people with disabilities are to different sectors of society. Even in the current scenario, there is – to date – no specific survey that highlights factors that pose a special risk of COVID-19 contagion to PWDs, be it through the use of assistive technologies, the need for support for basic activities, pre-existing health conditions, or even poverty. It is, therefore, appropriate to consider the more extensive use of risk communication to promote the visibility of people with disabilities in times of crisis and increase references to them in government pronouncements, drawing attention to the need to create emergency public policies for this most vulnerable group in society.