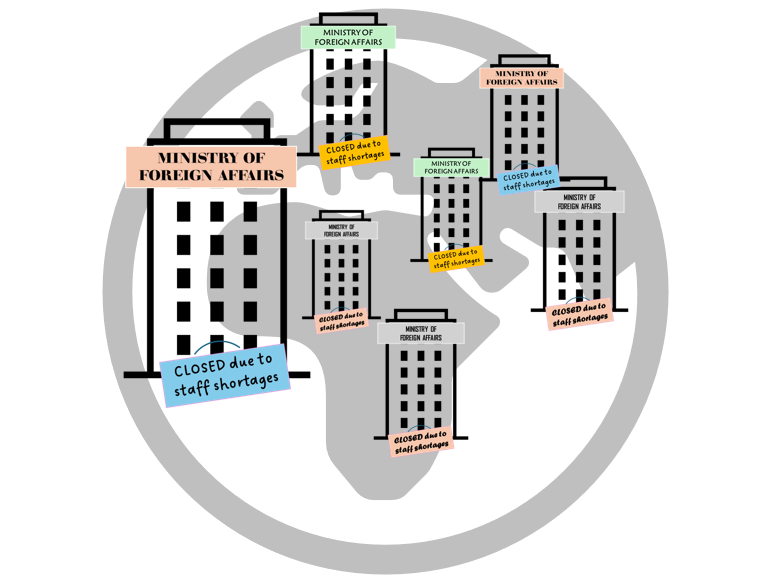

From the EU-27 to the US to India, foreign services are chronically understaffed. Beyond resignations of current diplomatic staff for a variety of reasons, youth interest specifically towards the public sector and diplomacy seems to be declining, while political apathy appears to be on the rise.

This begs the question as to whether there is a global diplomatic shortage, encompassing both a shortage of demand for and of supply of diplomats, the latter particularly among youth, and a shortage of resources. This article summarizes the main points of a forthcoming paper/study that aims to answer the following questions: (1) What factors serve as motivators and deterrents for young people to enter the diplomatic service in today’s environment?; (2) How might these contribute to driving a diplomatic shortage?; and (3) How can diplomatic human resources be reformed in order to curb this diplomatic shortage?

To answer these questions, the study conducted 33 semi-structured written and spoken interviews with 24 young people across 12 different nationalities, 5 professors of International Relations, Political Science, Public Policy, across 3 different nationalities, and 4 current diplomats, across 3 different nationalities. These interviews were then inductively coded by theme and analytical category.

The literature review we conducted confirmed the staffing crisis worldwide and indicated that there are a variety of political/state-based, personal, and wider socio-cultural reasons driving this personnel crisis. While some of these factors have always been held against the diplomatic profession, it is interesting to note that the majority stems from modern developments in the international affairs job market, the worldwide and national economies, and from key changes in social preferences and priorities regarding work environments.

Ultimately, and in line with the literature review findings, the interview results indicated that the diplomatic sector today is indeed facing a personnel crisis. Most young interviewees were interested in diplomacy, but not through MFAs; all professors indicated a significant decline in their students’ interest vis-a-vis the diplomatic corps; all diplomats but one recognised the existence of personnel issues. The reasons – which were streamlined in all responses – given for this declining interest were found to be personal (e.g., work-life balance, gender equality, family/spouse, less trust in the public sector), socioeconomic (e.g., opportunities in other fields, private sector competition, new technologies), and political (e.g., nepotism, political appointments, foreign policy priorities), and administrative (e.g., budget cuts, bureaucracy).

Nevertheless, all interviewees agreed upon the fact that diplomacy remains indispensable, but also that it should be evolving with the times and so should its human resources and mode of operation. Thus, on the one hand, many of the young interviewees still wish to become diplomats, but will either opt for other ways of producing diplomacy – via academia, civil society, or the private sector – or will reconsider the diplomatic dream overall citing the aforementioned reasons.

In trying to identify ways to address the driving factors of the diplomatic shortage, we believe that one element situated at the intersection of all of them is the need for changes within MFAs themselves, starting from their human resources departments. Reforming the diplomatic service hiring process should be the first step, and particularly adapting its content, both knowledge- and skills-wise, to the modern day international affairs environment, ensuring transparency, and avoiding opaqueness and nepotism.

After all, proceeding with such steps will increase the quality of the corps and, thus, the efficiency of foreign policy implementation which should be the goal of every MFA. In addition, addressing questions of gender equality in the workplace, of merit-based promotions alongside criteria stemming from each government’s foreign policy objectives, as well as addressing concerns over spouses’ professional development should also be considered. And, as with the public sector in general, leaving bureaucratic modes of operation behind in the name of efficiency constitutes a way to render the service more attractive.

Furthermore, MFAs should also fully embrace modern socio-economic developments and technology more efficiently, as these are leading to momentous changes in the job market, but also in how diplomacy is produced (e.g., citizen diplomacy, online embassies, etc.). The advent of Generative AI and automation further threatens to change the landscape at a rapid pace. MFAs should therefore adapt their staffing demands to these new circumstances.

Importantly, potential candidates should not be left out of the ‘need for change’ discussion. In fact, it is crucial for them to understand the quintessential elements of the diplomatic profession and, particularly, the high level of responsibility and danger it bears, as well as its interconnectedness with politics and public administration. Indeed, diplomats serve their country and its interest, yet they are bound to the present government’s political priorities. However, this should stop at the water’s edge, that is, for example, at merit-based promotions instead of the mushrooming of political appointees, an open ear for career diplomats’ professional opinion on any issue in order to fully utilise their expertise – irrespective of the policy eventually adopted on a ministerial level. Yet, in cases of complete ethical or political disagreement on behalf of a diplomat with a particular policy, resignation poses as the only option.