If you’ve ever wondered what post-postmodernism might look like, 2016 gives you a pretty damn good idea.

In 1993, Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s LDPR became the largest party at the Russian Federal Assembly, the State Duma. Since his campaign promises included cheaper vodka for men and better lingerie for women, nobody in their right minds ever took the guy seriously. After the election, one could often hear the ironic explanation “народ пошутил” (“the people have played a joke”). Can the “people’s joke” explanation also be applied to Donald Trump’s victory? Well, yes and no.

In any case, the US, yet again, has proved that it is way ahead of the rest of the world. Zhirinovsky, who is, unsurprisingly, also one of Trump’s avid Russian supporters, has never managed to climb above his current post as a jester in Putin’s court. Only in America could a jester dare to aim for the throne and actually get it. This will go down in history.

Facts don’t sell, not any more

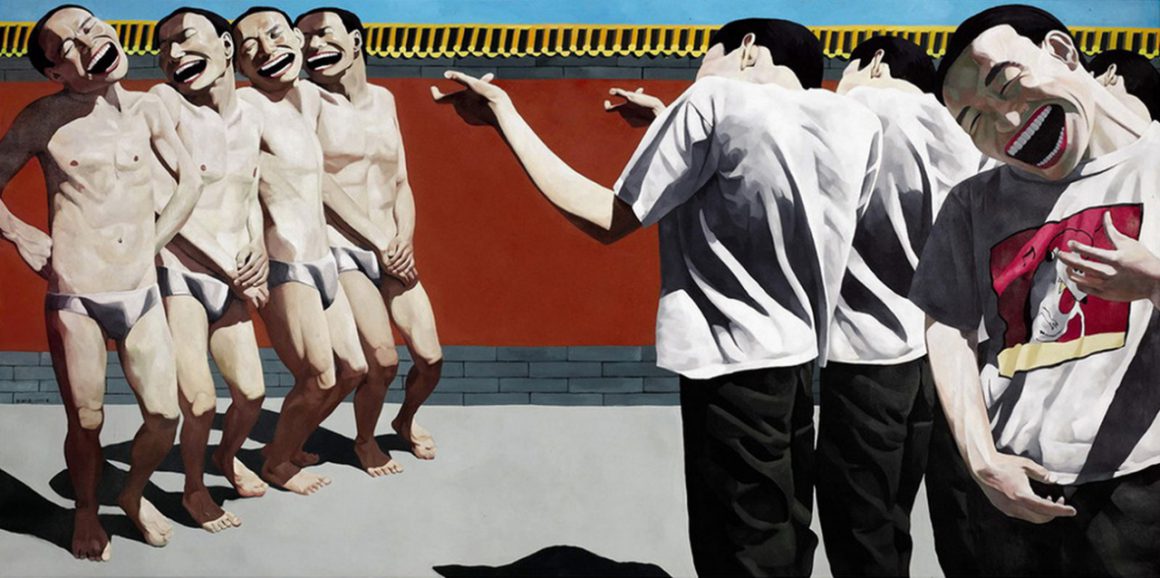

Reacting – and overreacting – to Trump’s victory, people bring up historical allusions and fears. Looking at Trump’s haircut, at his facial expressions and bodily gestures, at this entire absurd and ridiculous man, it is indeed difficult to brush off visual recollections of, say, Benito Mussolini.

“The current amazement that the things we are experiencing are ‘still’ possible in the twentieth century is not philosophical. This amazement is not the beginning of knowledge.” Walter Benjamin’s remark is still relevant in our own century, since this amazement still often comes at the price of thought and understanding.

The big media were as wrong with their polls and predictions about Trump as they were about Brexit. This will also go down in history. Yet, while brushing my teeth to the morning news after Trump was elected, I remember my impression that this getting-it-wrong has become more a rule than an exception. The media pundits were struggling to hide their secret enjoyment at having been wrong again, and their suspiciously uplifted self-reflection — “Who would have thought such a thing could happen?” — all too smoothly led over to the advertisement block.

The same commentators seemed amazed that just a few years ago presidential campaigns were all about facts, policies and mutual respect between opponents, and that now one can win by spitting bile and making two opposite claims in one breath . What the media people didn’t say is that, while earlier the news itself was mostly about facts, now it’s about something else. Their product has been transformed.

Sex sells. And when it comes to selling news, shock, astonishment, surprise — not facts — are the next best things.

One thing we have learned is this: sex sells. And when it comes to selling news, shock, astonishment, surprise — not facts — are the next best things.

Strangely, the internet — the very technology that is still held up as the biggest enlightener in the history of humanity — dramatically devalues facts, though not only because it makes it easier to spread disinformation and propaganda. In the age of Wikipedia and Google, facts seem to always be just a click away. But that which is easily available is also cheap and, hence, unattractive. The result of these rules of the market is that the internet’s potential to spread truth and knowledge remains largely unfulfilled.

The matrix is cosy

At this very moment, on enormous computer-farms, algorithms are bred to gather your personal information, observe, store and evaluate your every move online. They then selectively guess what you would like to read next and thus also decide what you shouldn’t know. These algorithms are secret — not conspiracy-theory-secret but know-how-secret — and fiercely guarded, since they produce fat revenues for Google, Facebook, and other big corporate players.

Around half of US residents get their news from social media (a growing trend). Do you? I do. And by now, you are probably well aware that your feeds and timelines are increasingly turning into perfectly comfortable echo-chambers that show you the world as you would like to see it. The world we see online is increasingly a filter-bubble reality. It’s comforting and it’s creepy. Like a porn site that knows your kink and shows you nothing else.

This I know from experience. When I travel to place X, I use Facebook to let my friends in X know when I’m coming, how long I’ll be staying, and perhaps give them my local mobile number. Last year, when I was planning to visit Israel I did the same. But this time, I also wanted to go to Ramallah and Bethlehem, and so I posted on my wall that I’ll soon be in “Israel–Palestine”.

To my surprise, this time around, my post provoked little enthusiasm. I wondered: Did my Israeli friends forget about me? Were they pissed that I want to visit “the Palestinian territories”? So I asked around — person by person — and… bingo! None of my Israeli friends had ever seen the post. My guess is that because it contained the world “Palestine” or, perhaps, due to the even more politically contested expression “Israel–Palestine”, they got it filtered out for them. Thank you, Facebook.

Now, I trust the machines and I’m well aware that the chances of this text reaching anybody who does not already agree with its theses are negligible.

Way beyond post-truth

‘Post-truth’ was elected 2016 word of the year by to Oxford Dictionaries. But is the term accurate?

After modern age optimism about the possibility of creating a perfect society resulted in Gulag and Auschwitz, a generation (or two) of postmodernists distrusted and fought all big narratives, universal theories, fixed conventions, traditions, ideologies, etc. Instead, they believed that it is only possible and admissible to self-consciously blend these narratives, creating ever more new and unstable models, world views and styles. It fit well with the hard reality of capitalism, under which both consumerism on steroids and economic precariousness urged people to adopt the rapid flow of constant self-reinvention.

Postmodernism was the true post-truth age. But the logic does not end there. It’s not the end of history and the initial post-truth is now over and done with. Trump’s victory heralds a new era. I’ll call it “post-postmodernism”.

Post-postmodernism is different. It’s more than a conscientious distrust for established truths. It’s a new and much more cynical way to go about truths and realities. Because no one seems to be able to fully stand up for any particular truth any longer, any truth seems as good — and as universal — as any other. If postmodernism was simply suspicious of universal claims, we now enter the age of a full-blown, digitally-powered global relativism.

For a postmodernist, there is no truth, but, clearly, there are lies. Our times have come full circle, as there seem to be neither truth nor lie, for both are the same.

For a postmodernist, there is no truth, but, clearly, there are lies. Our times have come full circle, as there seem to be neither truth nor lie, for both are the same.

And hence, we also seem to enter a post-knowledge era. If Christ prayed: “Forgive them Father, for they know not what they do” and Marx warned: “They do not know it, but they are doing it,” our own predicament is best described by Žižek: “We know very well what we are doing, but still, we keep doing it.”

In his recent documentary, Adam Curtis calls this “hypernormalisation”. And it’s not only individual world views that have been hypernormalised, it has happened to our elected governments too. As a result, nowadays, entire states act like people in a state of shock. Political vision is compared to psychosis and considered dangerous, while politics is reduced to technocratic management and muddling through one crisis after another.

Hypernormalisation is fun

On election night, some of Trump’s supporters stayed up late and gathered on New York’s Times Square to hear the victor’s speech. One of them commented on his expectations about Trump’s presidency as follows: “It’s gonna be great fun.”

Now, it has been official long enough. Trump is the first clickbait president ever. And you won’t believe what happens next. But as you know, most probably, it’s nothing worth mentioning.